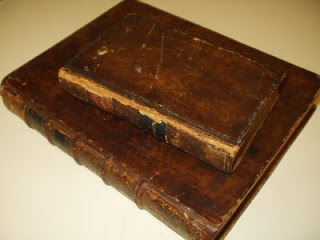

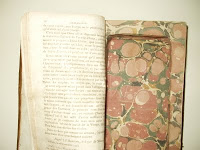

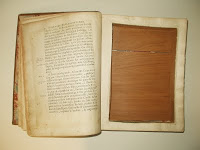

In the Clements Library book collection, one small shelf of books has the call number “Curiosa.” Here may be found oddities that fit nowhere else in the collection, including these two hollowed-out books. The smaller one is the Oeuvres choisies de Bossuet, volume 24 (1824), and the larger one is the Historie ecclesiastique par Monsieur l’Abbe Fleury, volume 1 of 20 (1722). Books like these provide an intriguing glimpse into the history of the book as an artifact. While most books are intended to be read, people have also used them for many other purposes such as decoration, furniture, or even storage.

In the Clements Library book collection, one small shelf of books has the call number “Curiosa.” Here may be found oddities that fit nowhere else in the collection, including these two hollowed-out books. The smaller one is the Oeuvres choisies de Bossuet, volume 24 (1824), and the larger one is the Historie ecclesiastique par Monsieur l’Abbe Fleury, volume 1 of 20 (1722). Books like these provide an intriguing glimpse into the history of the book as an artifact. While most books are intended to be read, people have also used them for many other purposes such as decoration, furniture, or even storage.

Such book boxes, also known as “book safes,” have a long history of use. They have been used to hide valuables from theft, smuggle weapons, drugs, and other contraband, and camouflage recording equipment and explosive devices. When backgammon was banned in England during the time of Henry VIII and all backgammon boards were ordered to be burned, people crafted them inside hollow books to conceal them. Hollow books were used during Prohibition to smuggle bottles of alcohol. Hiding an object in a book is also a popular plot device in fiction and film, including the movies From Russia with Love, The Shawshank Redemption, and The Matrix.

These book boxes were made by gluing the pages together, then cutting out the center of the text block and lining the interior. While hollow books may be considered delightful curiosities or useful hiding places by many, some book lovers can only regard the destruction of the book itself with horror. In The Anatomy of Bibliomania (2001), Holbrook Jackson eloquently writes:

“But what shall we say of those ghouls, chiefly in France, who scour the auction rooms, the booksellers’ shops and the stalls, for choice and ancient bindings which they turn into boxes by gluing the pages together, cutting out the type area, and so translating books into receptacles for cigarettes, cigars, liqueurs, jewels, chocolates, bon-bons, or note-paper? And what of those who encourage this ghoulish trade? They are no better than body-snatchers, desecrators of the temple, vain, tawdry, callous, whether sellers of such monuments of destruction or buyers of them, biblioclasts and dolts to boot, necrophils of a sort…”

A typewritten note inside the Histoire ecclesiastique, presumably written by a past book curator at the Clements Library, reads, “This shell, once a book, is not placed here as a curiosity, but as a shameful example. The existence of this kind of thing is the reason some people may not share in the joys of this library.”

If you want to try this at home, please don’t use a library book. Better yet, create a faux book by decorating a box to look like a book. Almost as good, but without the guilt, and then you can have fun making up imaginary titles to use for your faux book collection. Charles Dickens had a collection of such books, with entertaining titles like The Corn Question by John Bunyan, Dr. Kitchener’s Life of Captain Cook, and Mr. J. Horner on Poets’ Corner. Another fake library, described by Aldous Huxley, included such titles as Biography of Men who were Born Great, Biography of Men who Achieved Greatness, Biography of Men who had Greatness thrust upon Them, and Biography of Men who were Never Great at All.

Very interesting and fun!–especially the faux book titles.

Cool! I had no idea these were here. – Clayton

I have this book-the Historie ecclesiastique with the hidden compartment. I posted it on eBay before researching it. SO regretful that I did. I posted it among a large collection of vintage books I own and thought it was worthless. It's at $27 right now. Sheesh. Please share this link with anyone whom you may believe would be interested. Thank you.

http://www.ebay.com/itm/321198997286?ssPageName=STRK:MESELX:IT&_trksid=p3984.m1555.l2649

This is not the place for your eBay self-promotion. Honestly.

I rescue unwanted books from thrift stores that would otherwise go to recycling and make book safes out of them. Am I a desecrator of the temple?