Rationing is a common practice in wartime, meant to ensure that the country’s military is kept well-supplied without unduly depriving those civilians who can’t afford high-demand items back home. In some cases, rationing covers materials with obvious military uses, such as rubber tires and shoe soles, parachute silk, fuel, and automobile parts. In others, the focus is on food products, with the majority of certain staples being dedicated to the troops and war offices. This made formerly common foods and ingredients such as meat, flour, sugar, coffee, and milk difficult to obtain, and produced a new way of cooking that influenced the rise in processed and pre-prepared foods over the next few decades as well as unexpectedly introducing mainstream America to vegetarian and vegan food preparation.

The history of rationing during World War II is still fairly familiar to us these days, but rationing was also employed during the US’s involvement in World War I. A 1918 publication in the Clements collection entitled Conservation Recipes (full text also available via Google Books) is a collection of recipes and suggestions published by the Mobilized Women’s Organization of Berkeley, California. Along with a large number of recipes, the book gives advice on planning healthful meals–including school lunches–and using substitute ingredients for those items that were scarce, particularly wheat flour, sugar, and meat. “Food will win the War,” the book quotes (page 3), reinforcing the link between conservation and patriotic feeling. Curiously, the book’s emphasis on wheat-alternatives and natural fruit sugars make its recipes rather familiar to contemporary readers who follow a gluten-free diet or prefer to avoid processed foods.

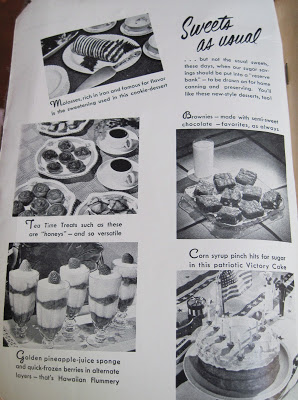

These parallels continue in the ration-conscious cookbooks of World War II, printed in an era where patriotic conservation was accompanied by patriotic production, of which the “victory garden” is one of the most famous features. Not only were cooks charged with reinventing the way they use food; they were encouraged to produce as much of their own as possible. The emphasis on healthy eating is also perpetuated, with government agencies urging citizens to make the most of their limited resources in order to maintain strong minds and strong bodies. “U.S. Needs US Strong,” proclaims a 1942 edition of The Modern Hostess Cookbook in an advertisement by the Office of Defense Health and Welfare Services. The cookbook, a special “Patriotic Edition,” also instructs that “these days… our sugar savings should be put into a ‘reserve bank’–to be drawn on for home canning and preserving” (2), and gives recipes that substitute molasses, honey, fruits, corn syrup, and semi-sweet chocolate for sugar in deserts.

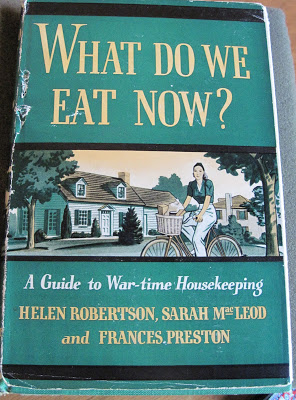

The book What Do We Eat Now? A Guide to War-time Housekeeping addresses the challenge faced by housewives struggling to keep a budget intact while providing the family with a healthy diet and doing her part for the war effort. With a constant emphasis on savings and thrift, and an encouragement to live up to the resourcefulness of her pioneer ancestors and her grandmother (who was, by age, likely a housewife during the First World War), the book provides resources, strategies, and recipes meant to maintain a pleasurable life while doing all possible to conserve resources.

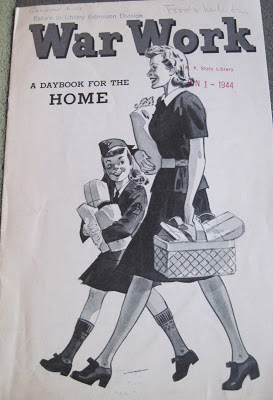

This emphasis on sustaining a positive attitude in the face of shortages can be seen in all of these books, from the extolling of alternative sweeteners for treats to the idea that a happy, healthy homeland makes for more successful troops abroad. As the 1942 General Mills publication War Work: A Daybook for the Home (pictured above) exhorts, “… every homemaker can make a contribution to victory. You will contribute to victory if you have the same goal in your home as the people in the armed forces, in factories and on farms: to win the war” (2).

Though women have long since moved beyond the household as their main form of economic participation, many of the ideas employed in these wartime manuals can be looked to as inspiration for not only healthy, tasty meals but for an attitude of optimism and survival in complicated times, whether during war or peace–certainly a lesson that can be applied today.

Ruth Berlozheimer and Edna L. Gaul, The American Woman’s Meals Without Meat Cook Book: starting eggs, high-lighting cheese, fish is a favorite, salads for summer, fresh & dried vegetables… (Chicago, 1943).

Alice Bradley, Desserts: including layer cakes and pies; with an introduction on desserts in war time (Cleveland, 1942).

Josephine Gibson, Wartime Canning and Cooking Book: Dedicated to the American Homemaker Whose Time is So Generously Devoted to the War Effort: Learn How to Make Cooking and Canning Easy: Substitutions, Balanced Menus, Meatless Meals, Ingenious Menus, Preserving and Canning. (New York, 1943).

Sheila Kaye-Smith, Kitchen Fugue (New York, 1945).