Page containing three images taken in Pinar del Rio, Cuba in July, 1899. Townsend himself likely took these and many other photographs that are present in the collection. Grosvenor L. Townsend Scrapbooks, Vol. 4, pg. 40.

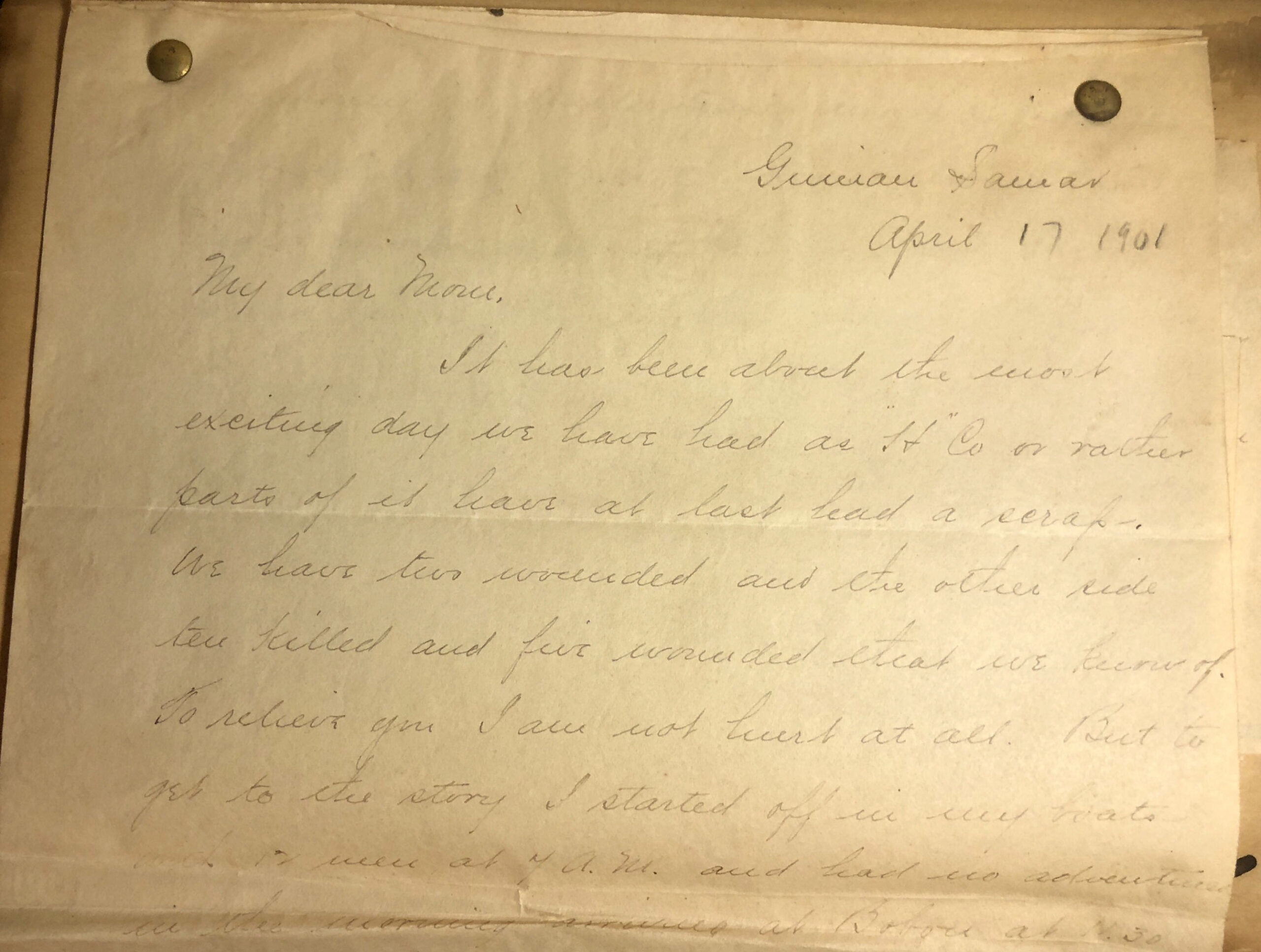

April 17, 1901 letter to Townsend’s mother Emma describing his first experience of coming under live enemy fire. Grosvenor L. Townsend Scrapbooks, Vol. 5, pg. 56.

Hand-drawn map from April 17, 1901 detailing the area surrounding the town of Guiuan in southeastern Samar. Includes references to locations of where an American deserter was supposedly killed, where an ambush occurred, and where Townsend came under live fire for the first time (across the bridge north of Mercedes, marked by the small flag symbol). Grosvenor L. Townsend Scrapbooks, Vol. 5, pg. 55.

Numerous newspaper and journal clippings illustrate how the U.S. Army’s conduct was being represented to the American public. Precious little sympathy is afforded to the Philippines, a nation that fell under the yoke of Spanish rule for almost three-and-a-half centuries only to see their long-awaited opportunity to establish independence ironically thwarted by the United States. The people of the Philippines were more often than not portrayed negatively as deceitful and untrustworthy. One article in the New York Herald from October 20, 1901 discussed the ongoing unrest in Samar and described the estimated 200,000 natives of Samar as “willing to do anything to advance their interests. They may live for months in the neighborhood of troops, and seem to accept the situation, admitting that American rule is what is best for them and taking the oath of allegiance. They may be sincere or they may be wearing a mask, waiting for the first opportunity to throw it off and change from amigos to enemigos.” A clipping of an extremely derogatory poem titled “The Gentle Filipino” also helps to underscore just how prevalent racist attitudes towards Filipinos were throughout the conflict.

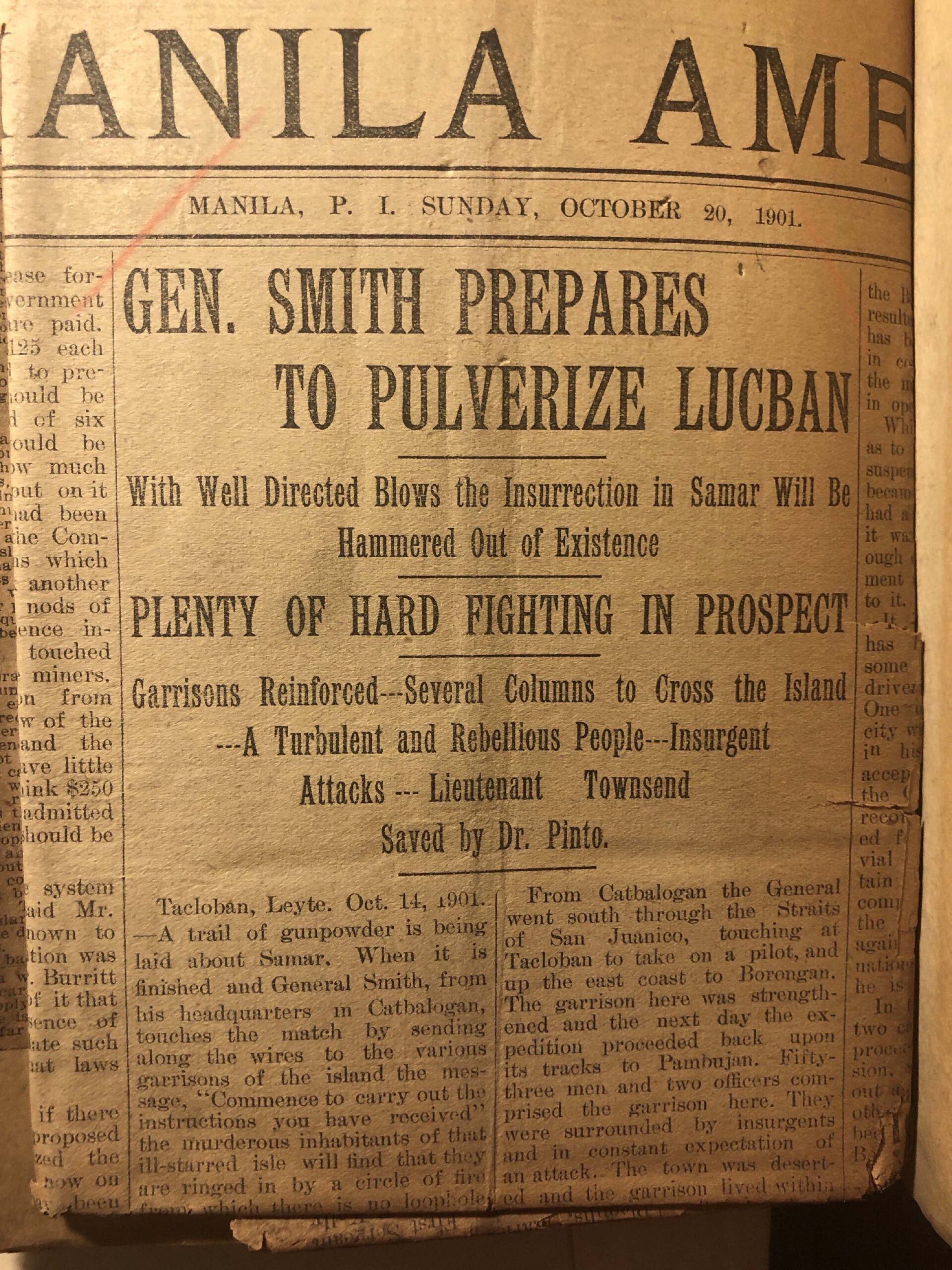

Loose issue of Manila Times newspaper from October 20, 1901, with front page article detailing counterinsurgency operations underway in Samar. This article also references an earlier incident from July during which Townsend was stabbed in the arm. Interestingly, the article’s portrayal of this event differs from what Townsend wrote about it. According to the article, it was one “Dr. Pinto” who came to Townsend’s rescue by shooting the attacker dead. In Townsend’s written account of this event, he claims to have shot his assailant twice at point blank range after his gun initially misfired. Grosvenor L. Townsend Scrapbooks, Vol. 5, pg. 76.

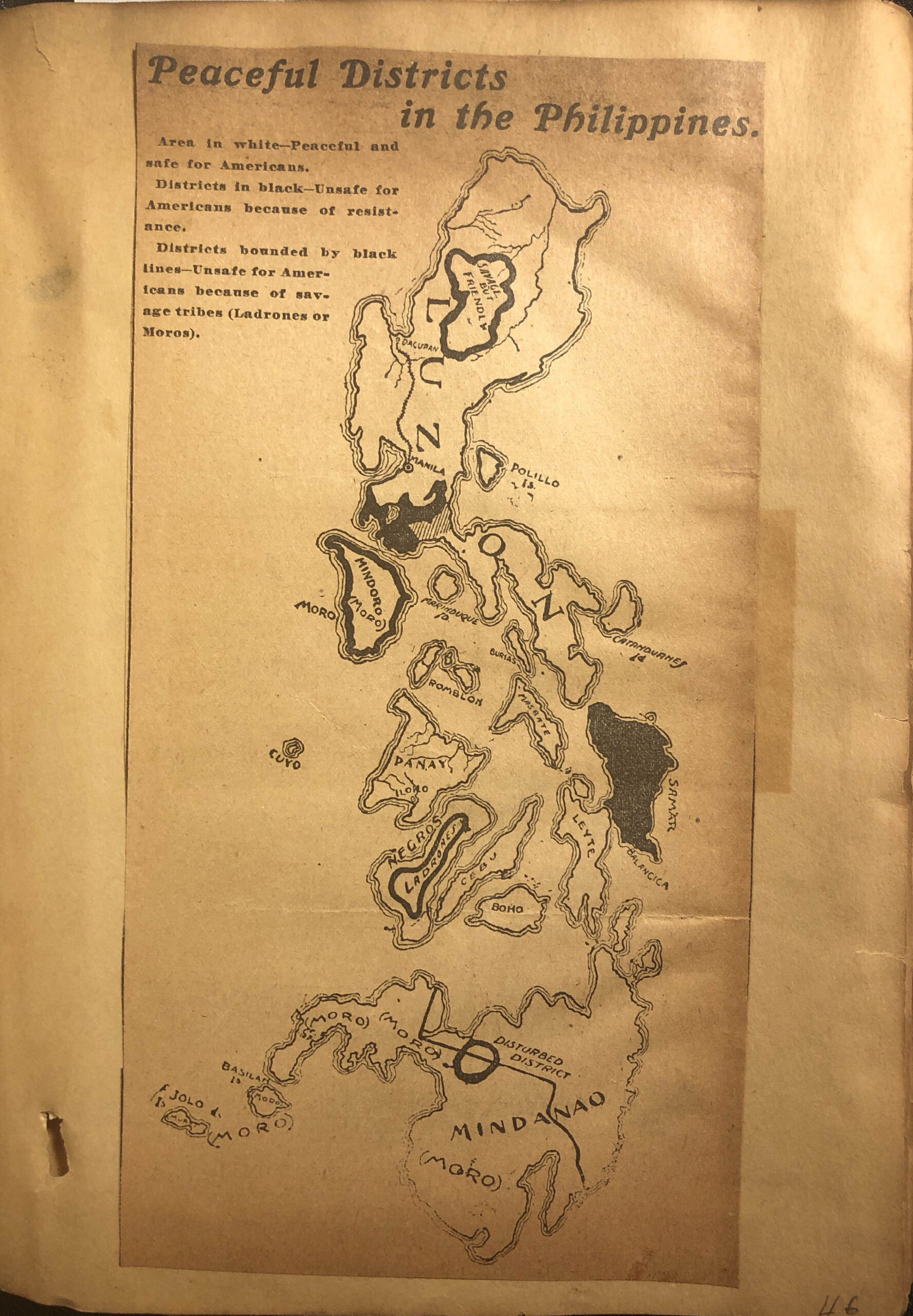

Undated clipping (possibly from March/April, 1901) showing map of the Philippine archipelago. Individual islands were color-coded to illustrate which regions were “Peaceful and safe for Americans” and which regions were unsafe due to ongoing resistance or because of the presence of “savage tribes.” Townsend spent much of his first tour in the Philippines involved in operations on the island of Samar. Grosvenor L. Townsend Scrapbooks, Vol. 5, pg. 46.

Many of the photographs that are present in the collection appear to have been taken by Townsend personally, possibly with a box camera. Among the plethora of images taken during his time in the Philippines, one set from his first tour touches on a peculiar aspect of photographic history. A cluster of eight images in Volume 5 document a visit by a group of curious tribesmen who had sailed to Samar from the nearby island of Palau in order to interact with American troops. The Palauan group happened to visit the encampment where Townsend was stationed, and he jumped at the chance to photograph the men on shore as well as during a demonstration of their sailboat. Townsend relayed the experience of the Palauan visit in a letter home in which he described the fanfare that the group’s presence generated among the Americans. He also mentioned that the Palauans were tattooed extensively, and yet if you look at the photographs he took (and which he intended to send home as soon as they were developed), there does not appear to be a single tattoo on anyone’s body. At first, I did not know what to make of this. Was Townsend deliberately exaggerating his description? If so, wouldn’t he have realized his mother would probably notice that the individuals in the photographs don’t have any tattoos? In fact, it appears that the reason for this strange inconsistency may boil down to technological circumstances. New Zealand-based photographer Michael Bradley recently conducted a study during which he photographed Maori men and women with traditional tattoos using both modern digital methods as well as 19th-century wet plate technology. Bradley found that while these tattoos showed up perfectly in the modern photos, they were rendered completely invisible in the wet plate attempts due to a lack of sensitivity to specific pigments present in the tattoo ink. It is possible that the equipment used by Townsend when photographing the Palauans was also equally incapable of properly capturing their tattoos.

Group portrait by G. L. Townsend of Palauan tribesmen who visited the American camp at Guiuan, Samar. In a letter to his mother dated April 20, 1901, Townsend described the group as consisting of ten men, the majority of whom “were tattooed all over.” Grosvenor L. Townsend Scrapbooks, Vol. 5, pg. 58.

On the whole, researchers should find the Townsend Scrapbooks to be a phenomenal trove of information that can support numerous angles of scholarship in the history of Philippine-American relations, the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars, and a great many aspects of United States Army organization and culture around the turn of the 20th century.

—Jakob Dopp

Graphics Cataloger