Mary Pedley, Assistant Map Curator at the Clements Library, is co-editor with Matthew H. Edney of The History of Cartography Volume 4: Cartography in the European Enlightenment (University of Chicago Press 2019).

* * *

The old adage about pictures and words has provided the editors of the History of Cartography Project with the formula for book design ever since the reference series, The History of Cartography, first appeared in 1984. A reference work on mapmaking must have maps and the first question a publisher asks is how many? Illustrations can devour a budget quickly: they take up space, they require special handling in reproduction and layout, they are costly if they require special permissions, and they are even more expensive when produced in color. Yet in the thirty plus years since that first volume appeared, digital technology has brought costs down and production values up. With the publication of Volume Four of The History, all 954 images illustrating the work are printed in color, and all were provided in a digital form.

In the case of Volume Four of the History of Cartography, a picture is worth 788 words (on average): 954 images of maps illustrate the 751,995 words that comprise 479 entries of this encyclopedic reference volume; they were supplied by over 200 archives, libraries, private collections, and map dealers in Europe, North America, Turkey, Russia, and even India. The University of Michigan joined this group by supplying 51 or 5% of the images in the volume. This number speaks to the breadth and depth of the University’s holdings and reflects the farsightedness of acquisitions made by earlier curators. Almost half of the Michigan contributions (24) came from the Clements Library, followed by those from the Clark Map Library, Special Collections, and the general collection of the Hatcher Graduate Library.

The maps that were imaged from the Clements reflect the chronological range of the *European* Enlightenment (ca 1650 to ca 1800) and the different mapping processes employed in Europe and its overseas colonies, specifically boundary, geographical, property, topographical, and urban mapping. Such maps informed and comprised administrative, military, and commercial enterprises, which are equally covered. Some maps in Volume Four will look familiar to Clements supporters, who have seen the manuscript maps from the Clinton and Gage papers in other contexts. Two such examples illustrate Brian Dunnigan’s entries on “Fortification Map” and “Battle Map”— articles that describe the contents, layout, and visual vocabulary of these standard types of 18th century military maps:

“Plan of Johnston Fort at Cape Fear,” manuscript map surveyed and designed by John Abraham Collet (1767)

A Clements regular will be pleased to see one of the sheets from the rare Murray Map of the St. Lawrence River, this one by John Montrésor of Lac Saint Pierre, a widening in the river downstream from Montréal, near Trois Rivières, which illustrates the entry on Topographical surveying in British America by Alexander Johnston.

Yet no one would automatically think of the Clements Library as the place to find a German map of Paraguay from about 1740 showing the location and limits of Jesuit missions in the region of the Rio Plata in South America. This map, based on the work of Jesuit missionary Juan Francisco Dávila, appeared at a parlous time in this region for the future of the Jesuit missions during the disputes between Spanish and Portuguese colonial claims. It also demonstrates the considerable contributions made by the Society of Jesus to mapmaking in general, thus illustrating aptly the entry on the Society of Jesus by Juniá Furtado.

“Paraquariæ provinciæ Soc. Iesu…” (ca. 1740)

The Clements Library holds numerous maps and atlases that reflect not only mapping efforts in the colonial setting but also maps that graphically display other concerns of the intellectual enterprise of the Enlightenment. The world map by Marie Le Masson le Golft required a long title to explain its goal: Esquisse d’un tableau général du genre humain ou l’on apperçoit d’un seul coup d’oeil les religions et les moeurs des différents peuples, les climats sous lesquels ils habitet et les principales varietés de forme et de couleur de chacun d’eux. That is: “Sketch of a general tableau of humankind, where one can see at a single glance the religions and mores of different peoples, the climates in which they live, and the principal varieties of shape and color of each of them.”

Marie Le Masson Le Golft (1749-1826) was a native of Le Havre in France, daughter of a sea captain. She studied with the naturalist Jean-François Dicquemare, was a member of the Cercle des Philadelphes, a scientific society based in Santo-Domingo (Haiti), and became a teacher in Rouen, writing prolifically on education. Like many other Enlightenment scholars, she was intrigued by the arguments of whether climate or environmental factors accounted for human variation. She used this world map as a graphic tool for representing a system explaining human variety by employing different symbols to distinguish between religions, customs, skin color, and physical shape. These are drawn on hemispheres that are divided into five temperature zones and twenty-four “climats” (regions based on the average length of days and nights). The map as a whole allows a reader to infer connections between geography and human variability and serves to illustrate the entry by Charles Withers on the “Enlightenment and Cartography.”

Another unexpected image from the Clements collection is the broadside in the form of a globe gore by Georg Moritz Lowitz, advertising the large globes produced for sale by the newly created Kosmographische Gesellschaft (Cosmographical Society) in Nürnberg in 1749. Lowitz, a member of the Society, proposed a three-foot globe and designed this gore to allow potential buyers to see one section of its proposed contents. The Latin title, Specimen trigesimae sextae partis ex globo terrestri trium pedum Parisin… [Sample of a thirty-sixth part of the three Paris foot terrestrial globe…] may not strike the modern reader as a successful advertising ploy, until we remember that Latin remained a lingua franca in the 18th century, understood by all educated readers in Europe, which explains its continued use for the titles of maps aimed at an international market until the end of the 18th century. At the same time, the place names on this globe are in a mixture of French, English, and Spanish. The Lowitz globe gore illustrates the entry on “Academies of Science in the German States” by Markus Heinz.

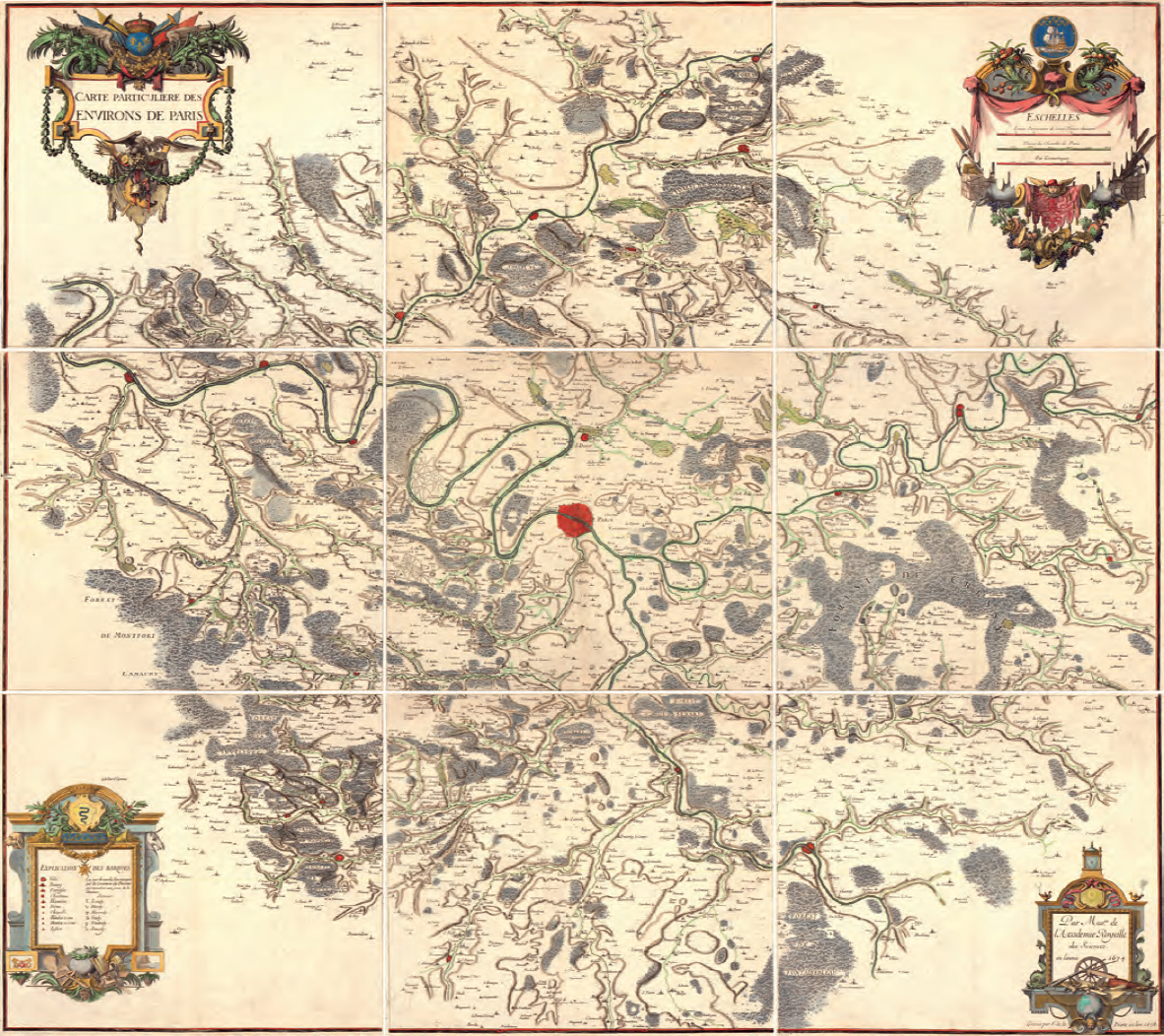

Our colleagues in the Hatcher Graduate Library next door added some beautiful and unusual maps to the illustrations of Volume Four. A stunning large map of the environs of Paris from 1678 is housed in the Clark Library and accompanies the entry on the “Académie des Sciences of Paris” by Isabelle Laboulais. The map was one of the first projects of the young Academy of Sciences, founded only twelve years earlier in 1666; the plan was designed and published to show the feasibility of using recently refined techniques of triangulation and the determination of longitude to more accurately locate places on the earth’s surface.

“Carte particulière des environs de Paris” / Par Messrs de l’Académie royalle des sciences en l’année 1674 ; gravée par F. de la Pointe en lan 1678.

The Special Collections library in Hatcher conserves an unusual German celestial atlas, the Neuester Himmels-atlas by Christian Friedrich Goldbach (Weimar 1799), which replicates the night sky as a black surface, with the stars shown on one plate by themselves, and on the facing plate with the outlines of constellations and the grid of a celestial coordinate system shown. It illustrates the entry on “Celestial Mapping” by Matthew Edney. The constellation shown is Aquarius (the Watercarrier); the black colored printing is created by the engraving technique of mezzotint.

This small sampling of the 954 images in Volume Four of The History of Cartography will, I hope, whet your appetite to look at this volume more closely when next you come into the library or to learn more about acquiring your own copy.

— Mary Pedley

Assistant Curator of Maps

***

Other places to find out more about The History of Cartography in the European Enlightenment:

- The co-editors of the volume are interviewed on the blog, The Learned Pig: http://www.thelearnedpig.org/the-history-of-cartography/9384

- Follow The History of Cartography Project on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/HistoryofCartographyProject