The hurricane season has once again seized our attention as enormously powerful storms form over the North African desert and move out to sea, drawing up moisture as they drift westward. Concern for family members who have moved to a warmer climate (and for permanent residents as well) draws more public awareness than usual to the waters south of the United States and help remind us that the Clements Library is not just a repository documenting mainland colonial and nineteenth-century America. The Library also preserves primary sources of other regions of the Americas, including the Caribbean. Although this electronic newsletter has previously trumpeted our West Indian holdings, these comments come as a reminder that our delightfully diverse collections continue to grow and include West Indian naval and military history, plantation life, commerce, production, agriculture, the sale and exploitation of enslaved people, natural history—from seahorses to big cats—and the life experiences of slaves in the Americas in an atmosphere swarming with sweat, squalor, and violence.

|

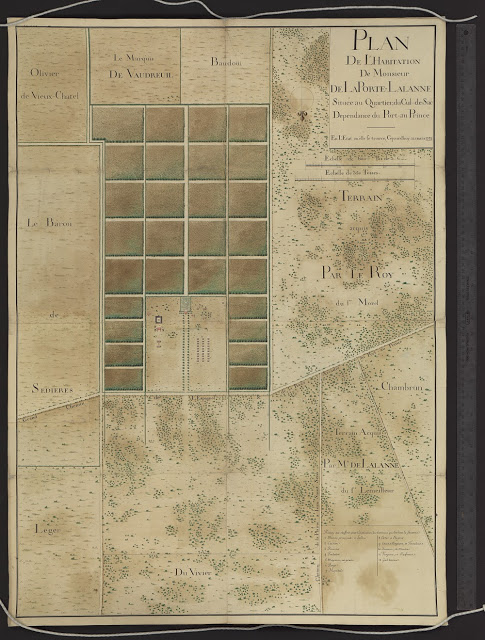

| “Plan de l’habitation de monsieur de La Porte-Lalanne située au quartier du Cul-de-Sac, dependence du Port-au Prince: En l’état ou elle se trouve cejourd’huy 12 Mars 1753.” |

Over the last few years the Clements Library has been fortunate to acquire a considerable quantity of new documentation relating to St. Domingue as colonial Haiti was called. The eastern half of the island of Hispaniola had become a Spanish colony, today the Dominican Republic, while the western half (Haiti) went to France. By the middle of the eighteenth century, St. Domingue was the richest colonial possession of France, its wealth based on sugar. The French Revolution changed that as different segments of its diverse population reacted in differing ways to events in Europe. Slave uprisings, inter-class violence, foreign invasion, and civil war repeatedly shook the colony. The situation was further complicated by British intervention and attempts by the French republic, and later the empire, to reestablish metropolitan control. Haiti slid into poverty and instability and has never fully recovered. Natural disasters, such as the devastating earthquake of 2010, have made improvement even more challenging. Today this painful history has helped make Haiti the poorest nation in our hemisphere.

Scholars have not overlooked the Clements Library’s strong and growing collections on colonial and revolutionary Haiti. In recent years a number of U-M history faculty have mined our holdings on Haiti while encouraging us to continue acquiring primary source material. Recent additions include small collections of manuscript material from the 1790s and a French attempt to bring the colony back under metropolitan control in 1798; dramatic full-color prints depicting the burning of Cap Français and the nearby plantations in the early 1790s; and, most recently, a revealing and beautifully rendered manuscript plan of a sugar plantation situated just east of Port au Prince.

This latest addition to our Haiti material is also one of the most attractive pieces of cartography in a map collection that stands out for its high quality. Like many of our recent acquisitions, it was acquired in France and surpasses all of our other property plats in its artistic technique and the information it provides about the organization and operation of an eighteenth-century sugar plantation. This 96 x 71 centimeter work was drawn in 1753 by a talented but unidentified surveyor. It is titled “Plan de l’habitation de monsieur de La Porte-Lalanne située au quartier du Cul-de-Sac, dependence du Port-au Prince: En l’état ou elle se trouve cejourd’huy 12 Mars 1753.” The plantation’s crop fields are divided into 28 neat parcels. All are shown as cane fields by the realistic rendering of the fields of tall stalks that must have been visible as far as the eye could see. Large parts of adjoining properties appear around the boundaries of M. La Porte-Lalanne’s plantation, all labelled with the names of their proprietors. One of them was Pierre Rigaud de Vaudreuil, Marquis de Vaudreuil (1698-1778), who was just ending his service as Governor of Louisiana in 1753 and who was fated to be the last Governor of New France (1755-1760).

|

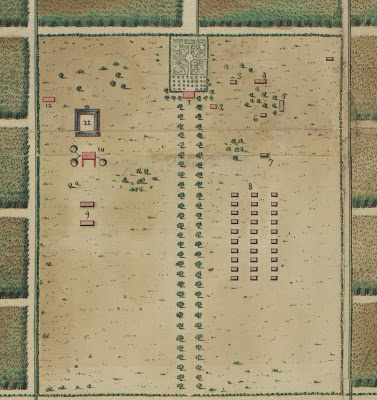

| Close-up view of the plantation portion of the map. Click to enlarge. |

One block stands out from the sea of sugar. It is clear-cut with the only trees being ornamentals or those bordering the drive to the buildings of M. La Porte-Lalanne’s plantation. This part of the plan is the most informative, showing how sugar production was related to the facilities available and the organization of the infrastructure. The Clements has at least one similar plan depicting the layout of a plantation in Haiti (also dated 1753), but it lacks a table of references to identify the structures. Our new arrival has many similarities in its layout, and the two plans could also be compared with others to determine if there was a consistent pattern in the organization of a plantation’s infrastructure.

All of the structures of are numbered, and a table of references presents an Explication of the buildings, identifying them in some detail. The numbers of the table commence with the plantation’s élite, the owner and his family. “1” is the “main house” or mansion, and nearby is a carefully designed eighteenth-century formal garden. The kitchen for the mansion is number “2.” It is located in a building set well apart from the main house to reduce the threat of fire, the equivalent of the summer kitchens so common in the American South. The coach house is number “3.” M. La Porte-Lalanne’s property bordered the primary road to Port au Prince, and a coach or passenger carriage was a necessity when someone of his status wanted to go into town. Number “4” is the hen house, located not far from the kitchen.

The remaining structures take us into the gritty, industrial part of manufacturing sugar from cane. Number “5” is identified as the storehouse for grain, and “6” is the forge from which a blacksmith maintained tools and equipment. Set at some distance from any of the habitations is the hospital (“7”), while some distance to the north (north is at the bottom of this map) are three long rows of “cabins of the Negroes” (“8”). Number “9” identifies an area for the storage of waste and, nearby, a cooperage for the manufacture of barrels. Many of the craftsmen were probably part of the enslaved population.

The true heart of the plantation is represented by numbers “10” through “12,” the sugar works with a trio of mills for grinding the cane, and “11,” the refinery or boiling house where the sugar water was removed from the waste cane. Finally, number “12,” the brewery, probably made beverages for local consumption.

The 1753 plan of the buildings of M. La Porte-Lalanne’s sugar plantation provide a model and a check list of the infrastructure of a large-scale sugar operation. Used with other plans, documents, and published works about St. Domingue and sugar-making, this new arrival can give us more insights into sugar and slavery in the Caribbean.

Brian Dunnigan

Associate Director and Curator of Maps