Guest post by Allison K. Lange, assistant professor of history at the Wentworth Institute of Technology. She helped curate the Leventhal Map Center’s “We Are One” exhibition.

|

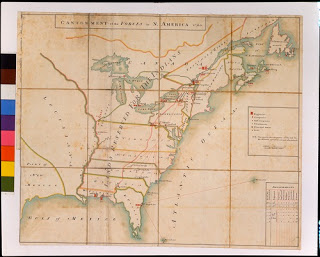

| Cantonment of the Forces in North America 1766. 1766. Manuscript, pen and ink and watercolor, 20.5 x 24.5 inches. |

The nearly decade-long French and Indian War ended with a British victory and the acquisition of new land in North America. The aftermath of the war, however, actually paved the way for the uprisings that led to the American Revolution. A 1766 map in the Clements Library’s collection gives us insight into the reasons behind the colonists’ rebellion.

Drawn by hand after the end of the war, the Cantonment of the Forces in North America 1766depicts the placement of British military garrisons. Each red rectangle represents a group of soldiers—a regiment, company, or half company depending on the rectangle’s size—stationed to defend the colonies, about 7,500 soldiers in total. This map reveals that most soldiers were on the borders of New York, Pennsylvania, Florida, and southeast Canada. Troops manned these areas to protect them from Native American tribes and other foreign powers. They also aimed to establish British authority among populations who had previously identified as French or Spanish.

The author of the map created it so that the government and military knew the placement of their troops. They monitored the movement of soldiers to ensure British control of the original colonies and newly won land. The map simplifies geographical features so that this information stands out. Unlike engraved and printed maps for mass circulation, this manuscript map was unique and intended for smaller audiences of elite government administrators.

The high costs of these garrisons and their soldiers were a significant reason for the American rebellion. The French and Indian War and the continued defense of the colonies required additional funding from the colonists. The government levied taxes to pay for the troops featured on this map. The 1765 Quartering Act required local governments to house and provide soldiers with provisions. Although the placement of the garrisons in the borderlands meant that the act affected few inhabitants, colonists resented the additional expenses. The Quartering Act along with the other infamous taxes of the 1760s—the Sugar Act, Stamp Act, and Townshend Act—led to rebellions throughout the colonies to challenge the British government.

The Cantonment map also features the Proclamation Line along the Appalachian Mountains. Although Britain gained new western land from the French after the war, the Proclamation of 1763 declared that colonists could not settle west of this line. Western lands were set aside for Native Americans. The mapmaker calls attention to this area by labeling it “LAND RESERVED FOR THE INDIANS.” The Proclamation Line infuriated colonists. Many ignored it, settled west of the boundary, and demanded British protection anyway.

British officials commissioned maps like this one to visualize their efforts to control the colonies. The Cantonment map is one of five similar maps drawn between October 11, 1765 and the summer of 1767 for the Quartermaster General. Together they show the movement of garrisons in North America. The Clements Library has one, and the Library of Congress and British Library house the remaining maps. The earliest two maps, including the copy owned by the Clements Library, are unsigned, but Ensign Daniel Paterson signed the latter maps. The similarities in the styles suggest that he likely drew the Clements Library’s version as well. Paterson used existing maps (possibly Thomas Kitchin’s 1763 map), rather than a new survey of his own to document the garrisons. He drew the maps in London and may have used correspondence from General Thomas Gage to document the location of the troops.

Paterson and the officials who used his map could not have envisioned the Revolutionary War a decade later, but, for modern viewers, this map features important details that highlight some of the major causes of the American Revolution. Colonists believed the government levied taxes without their consent and restricted their freedoms. Though he did not realize it at the time, Paterson documented the seeds of discontent on his map.

The Clements Library’s Cantonment map is currently on display at the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center’s exhibition at the Boston Public Library. The exhibition, We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence, uses maps to explore the events that led thirteen colonies to forge a new nation. We Are One demonstrates that maps, from the Cantonment map to early European maps of the new nation, were central to the revolutionary process. The exhibition features maps as well as prints, paintings, and objects from the Leventhal Map Center’s own collection and those of twenty partners, including the British Library and Library of Congress. Visit zoominginonhistory.com to explore geo-referenced maps from the exhibition.

The exhibition will be on display at the Boston Public Library through November 29, 2015. We Are Onethen travels to Colonial Williamsburg from February 2016 through January 2017 and to the New-York Historical Society from November 2017 through March 2018.

The Leventhal Map Center also hosts the NEH-funded American Revolution Portal database. Researchers can access maps from the British Library, Library of Congress, and other institutions in one search. Users can download images for research and classroom use. Access these resources and learn more about We Are One at http://maps.bpl.org/WeAreOne.

For more on this map, see Brian Leigh Dunnigan, “Mapping an Army in North America,” in An Americana Sampler: Essays on Selections from the William L. Clements Library (Ann Arbor: William L. Clements Library, 2011).