By Jonathan Beecher Field

In the fall of 2023, I had the privilege of being the Laramy Fellow in American Visual Culture at the Clements Library to pursue my interest in their extensive 19th-century ephemera holdings. My research trip to the Clements was part of a book project titled The Objects of Settler Innocence, which argues that a constellation of physical objects — road signs, historical monuments, cartoons, pinups, sexy Pilgrim costumes, and Thanksgiving-specific salt shakers, work to obscure the realities of settler colonialism for its present-day beneficiaries.

One aspect of this argument is a phenomenon I am calling “settler kitsch.” Settler kitsch is my name for the ubiquitous renderings of the Anglo-Indigenous encounter as something that is impossible to take seriously. These representations can take several forms, including pinups of Marilyn Monroe and other models dressed like sexy pilgrims, Precious Moments figurines, Laurel and Hardy dressed like Priscilla and John Alden (with Laurel in drag), sexy pilgrim Halloween costumes, Thanksgiving episodes of TV sitcoms, the trope of an Indigenous arrow passing harmlessly through the crown of a Pilgrim hat, and even Arthur the Aardvark dressed in pilgrim garb. In particular, settler kitsch manifests itself in the litany of images and texts that represent Anglo-Indian relations as a comedy with the kind of cartoonish whimsy and violence one sees in a Tom & Jerry cartoon. The danger of these images is not that they mislead, but that they distract and desensitize.

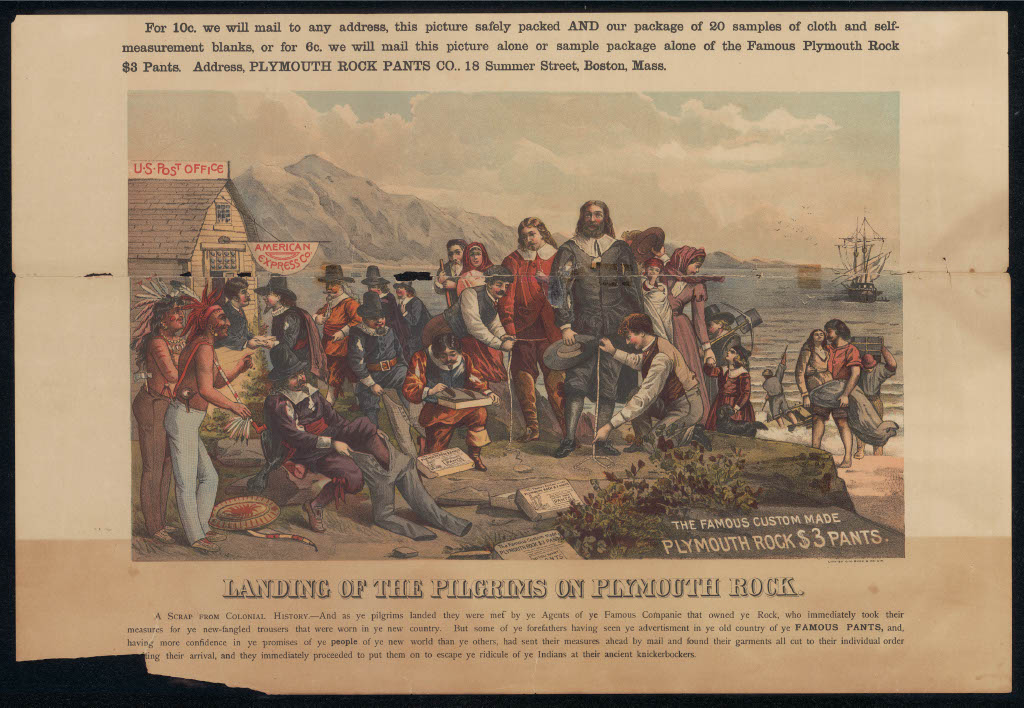

To my very good fortune, the Clements acquired a remarkable artifact shortly before I arrived. As you can see, it is a poster for Plymouth Rock Three Dollar Pants, evidently from the mid- 1890s. I found a hoard of useful images during my week at the Clements, but none as weird as this. It is a lampoon of the landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth, but this time, the focus is on pants.

Bettman. Marilyn Monroe Posing with a Turkey. Getty Images, 1950, https://photos.com/featured/marilyn-monroe-posing-with-a-turkey-bettmann.html

Precious Moments. Limited Edition Gather Together With Grateful Hearts Figurine, n.d., https://www.preciousmoments.com/limited-edition-gather-together-with-grateful-hearts-figurine?srsltid=AfmBOooLIExjk9j6Lr3LgklnSOhqtLseNagxcC3s9R96-2UoWZ2wY8wE

Massachusetts Turnpike Authority Sign. Road Traffic Signs, n.d., https://www.roadtrafficsigns.com/mass-pike-massachusetts-turnpike-authority-sign/sku-k2-5826

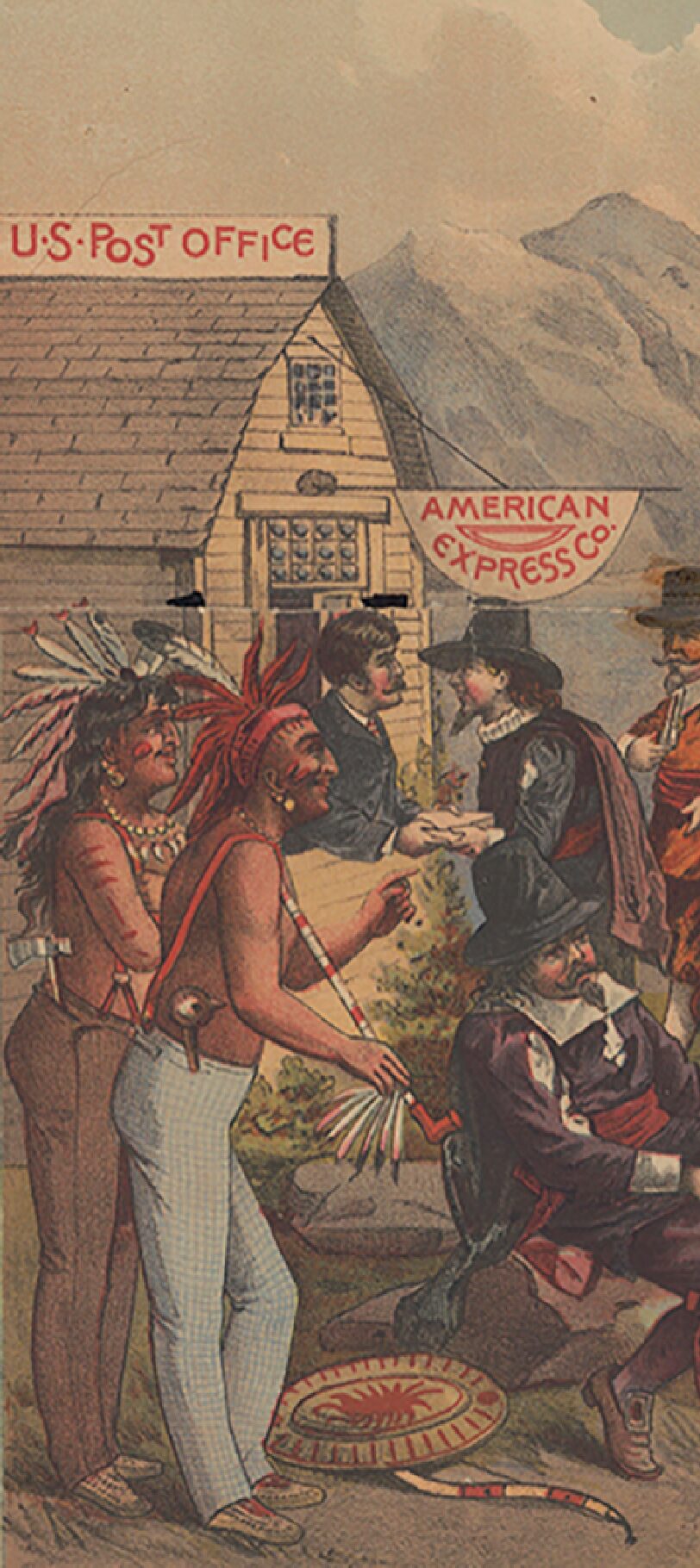

At the far left of the image, we see two shirtless Indians, sporting pants. Behind them is a post office and American Express station, staffed by a white man in 19th-century dress, and a line of pilgrims waiting to pick up their pants. In the center of the image, we see two pilgrims putting on their new Plymouth Rock pants over their old knickers, another pilgrim opening his package of pants. Moving right, we see two white men in 19th-century dress measuring a figure who seems to represent William Bradford. Behind Bradford, we see women and children who have just disembarked from the Mayflower, which is off in the distance. In what may be either a coincidence, or a cruel joke, we see an unconscious woman in the arms of a 19th century lifeguard, which might or might not be a reference to Bradford’s wife, who took her own life by jumping overboard on the voyage to America.

There is a caption below, using “ye” for “the” and other putatively old fashioned linguistic tropes to explain that some of the pilgrims had sent their measurements ahead of time, and had their “new-fangled trousers” ready for them at the post office, while other

pilgrims failed to do so, and had to get measured on the spot. As the caption makes clear, all of the pilgrim men felt compelled to discard their “knickerbockers” for Plymouth Rock pants to “escape the ridicule of the Indians.”

One of the hallmarks of a certain kind of humor is anachronism. It is, for some reason, amusing to see something that does not belong in the context of the scene. For instance, in Blazing Saddles, set in the 19th century Wild West, we see Sheriff Bart riding through the desert on his way to Rock Ridge. The music appears to be the sort of background music we expect in films but as the sheriff rides along, he encounters the Count Basie Orchestra, which is playing this music in the middle of an Arizona desert. Count Basie daps up Cleavon Little, we laugh, and he rides on.

As Jean O’Brien details in Firsting and Lasting, one of the foundations of settler colonial ideology is the exclusion of Indigenous people from modernity. As such, seeing an Indigenous person using a smartphone might elicit a “joke” about smoke signals. As such, anachronistic representations of Indigenous people can work in a variety of ways. Here, the joke, such as it is, is to represent Indigenous people as more sophisticated and modern than their English counterparts, while the audience for this advertisement would have understood that the opposite was true. Gags that work by presenting the opposite of a familiar stereotype are commonplace, and they work to reinforce a stereotype, even as they putatively subvert it. To choose a familiar example from the same film, Mongo, the subliterate behemoth played by former defensive tackle Alex Karras, surprises and delights us when he opines “Mongo only pawn in game of Life.”

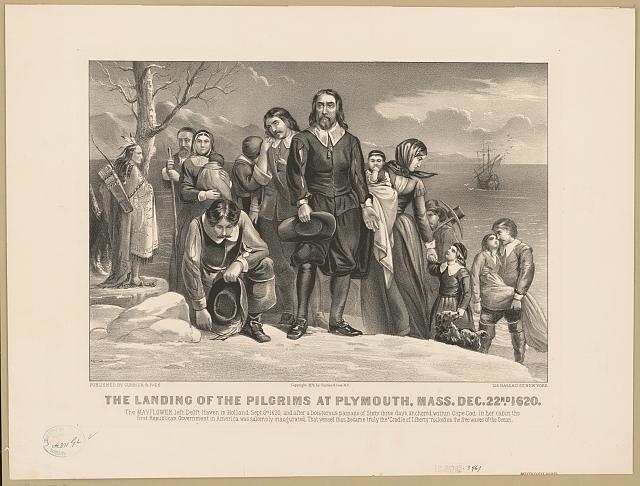

The purpose of this image was to sell pants, not to offer a realistic representation of the landing of the pilgrims. It would be foolish, then or now, to complain that this image is inaccurate, but it is worth considering as part of the host of distorted images representing this era that have proliferated in our culture. For instance, the bas-relief in the US Capitol depicting the landing of the pilgrims – from what we know, the pilgrims were not greeted by a kneeling Indian offering an ear of corn.

Currier & Ives. The landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth, Mass. Dec. 22nd. Massachusetts Plymouth, ca. 1876. New York: Published by Currier & Ives, 125 Nassau St. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2002707741/.

Seal of Providence, Rhode Island, 1878, Wikipedia Commons, https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Seal_of_Providence,_Rhode_Island.svg

Seal of Brockton, Massachusetts, 1951, Wikipedia Commons, https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Seal_of_Brockton,_Massachusetts.svg

Seal of Scituate, Massachusetts, 1951, Wikipedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Seal_of_Scituate,_Massachusetts.png

That said, the proliferation of images like this bas-relief, naturalize the notion of an encounter that was peaceful and friendly. The value of a library like the Clements collecting ephemera like this pants advertisement is that it shows the notions of pilgrims and Indians that were present in mass culture. It is my hope that putting a spotlight on obviously distorted representations like this advertisement will enable us to look at more benign representations of this encounter with a more critical instance. If you live in New England, there is a good chance that the town seal on the garbage truck or tax notice has a seal featuring a congenial encounter between settlers and indigenous people. The seal of Providence, Rhode Island, might be the most familiar case, but we also see this dynamic in the Massachusetts seals of the city of Brockton and the town of Scituate. We know that the Wampanoag were not selling pants to the Pilgrims, which might make it easier to see that the more plausible friendly encounters are also fabrications.

In his definitive essay “Avant-Garde & Kitsch,” Clement Greenberg, an art historian, focuses on the visual arts. My academic training and scholarship has been focused on words, but the Clements’ unsurpassed holdings in 19th-century graphics were key to my research there. For a kitschy 19th-century text like “The Courtship of Miles Standish” there are both primary and secondary accounts that shed light on the grim realities of Plymouth in its early years. There are no corresponding visual images. As such, what we “see” when we see images of pilgrim and puritan settlers are mediated through the imaginations of 19th and 20th century commercial artists and cartoonists. Understanding and detailing these distortions are a critical part of coming to a better understanding of the grim realities of settler colonialism.

Jonathan Beecher Field, Department of English, Clemson University.