Post by Clayton Lewis, Curator of Graphic Materials

|

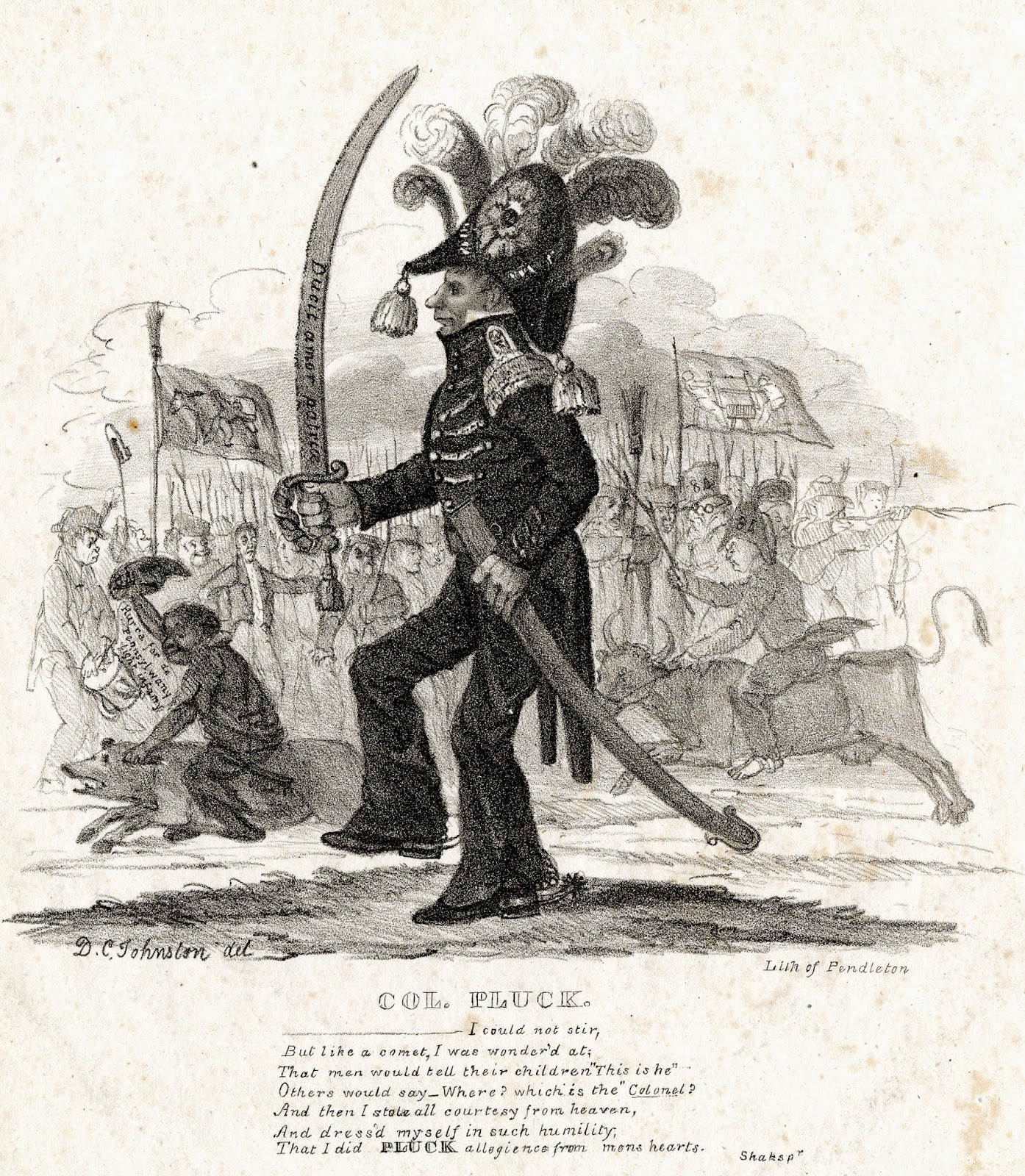

| David Claypoole Johnston. Col. Pluck. [Boston?] : Pendleton, lithographer/publisher, circa 1825. |

A pair of recently acquired prints point to a little known episode in American military history and pose questions about where satire ends and factual evidence begins. Satiric criticism is strongest when there is an element of truth behind the ridicule, but when the subject is already itself a parody, is the artist acting in collusion with the parody or simply reporting the facts?

The engraving Col. Pluck, by prolific parodist David Claypoole Johnston (1798-1865), shows a bawdy, disorganized, misbehaving, undisciplined American militia unit and its foppish leader. This image may in fact be a fairly accurate representation of a specific Pennsylvania unit and its commander’s carefully contrived appearance. The antics of Colonel Jonathan Pluck and the “Bloody 84th” Pennsylvania Militia from Philadelphia, as described in newspapers from Boston to Richmond in the 1820s, are close to matching the scene depicted.

During the period between the Revolutionary War and the Civil War, state militia units, prescribed by the Constitution of the United States, played a key role in national defense and greatly outnumbered the standing army. Militias were also a source of tension and resentment between classes as privately sponsored volunteer units rubbed against state compulsory militias along class lines. The necessary purchase of uniforms and weapons, coupled with time away from paying jobs, made required participation doubly expensive for the working poor. Resentment simmered under militia leadership self-selected from the leisure class, rising to the boiling point when that leadership was incompetent and/or corrupt. A crisis rose during the 1820s and 1830s as the general public lost faith in the ability of the militia structure to protect the populace. When efforts at reform from within failed, a creative and outrageous protest emerged from enlistees.

The urban environment of the 18th and 19th centuries had often witnessed collective celebrations, political demonstrations, rallies, and social protests in public spaces. Inaugural parades, hangings in effigy, mock funerals, and public humiliations were all part of the street culture of America’s larger cities. Philadelphia saw public parades in support of the Declaration of Independence, a two-headed Benedict Arnold paraded and hanged in effigy, a solemn mock-funeral for President Washington, and many other examples of street theater.

In this context, the enlistees of the 84th Pennsylvania Regiment from the dockyards and shops of the Northern Liberties district of Philadelphia were likely very conscious of the public spectacle that would result with the election of a colorful hostler from the stables in a tavern district, Jonathan Pluck, to the position of colonel of the regiment in May of 1825. Pluck, described in Niles Weekly Register as a “poor, ignorant, stupid fellow,” was elected not because he was seen as particularly well qualified for the position; he was seen as conspicuously unqualified. The rank and file elected Pluck as a pointed rejection of the officers placed by the circumstance of class and title. Reportedly, the state Governor refused to ratify the election, forcing a revote. The second ballot had Pluck winning again, with even more votes. The 84th would get the officer they wanted and deserved.

The results were reported in the Philadelphia Gazette the following day under the headline “Grand Farce.” When the 84th was on parade, crowds gathered. Pluck rode at the head of a deliberately ragtag, irregular, anti-orderly militia unit that wore mismatched uniforms and carried brooms and cornstalks in place of weapons. The story was picked up by papers up and down the country. The Democratic Press reported that “No one talks of anything else.”

“The events of this eventful day, which will ever be memorable in the annals of Pennsylvania chivalry, are the cause of the lots of merriment contained in the aforesaid Philadelphia papers” stated the New York Commercial Advertiser. Pluck led his 84th militia through Philadelphia to the Bush Hill mustering ground. The Advertiser reported “It was with great difficulty a person of ordinary activity and strength, could obtain a sight of the great object of such universal solicitude.” His appearance was described as hunchbacked, bowlegged in the extreme, with baggy burlap pants cinched by an enormous belt and buckle, bulging eyes and a huge head topped with a massive tri-cornered hat, all mounted on a sagging white nag of a horse. “Napoleon was low in stature, Pluck is lower still.” The Washington Reporter was preoccupied by his boot-spurs, stating that they were “the most singular part of his accouterments . . . made of iron and weighed better than one pound and three quarters… on which was suspended a small bell. The rowel of the spur was three inches and three quarter in diameter, and the whole length of the shank from the heel was better than five inches . . . an enormous length, and would have had a fine effect but that they occasionally, unintentionally gored his charger’s flank… [which was] rather lean to be sure.”

Colonel Pluck and the 84th had made their point and amplified the ongoing debate on the subject of the readiness of the militia. Although ridiculed for a presumed mental incapacity, Pluck seems to have understood the meaning of his role and when compared with other officers stated “well, at least I ain’t afraid to fight, and that’s more than most of them can say!” Pluck was both lauded and deplored in editorials and letters to the press as he toured with the 84th from New England to Virginia. Other state’s militias followed in self-mockery, going to further extremes of ridiculous dress and behavior. The prank had become a movement.

It all seems a ludicrous joke today but many of Pluck’s contemporaries saw his ascension as a serious threat. It wasn’t just the competence of military officers that was being called into question by Pluck’s presence; he also represented an infectious critique of the social order, in step with Andrew Jackson’s aggressive populist politics. Pluck did not help his own cause by charging admission for an audience. “He exhibited himself at a shilling a sight, to the infinite dishonor of the venerable 84th, which he commands.” The Philadelphia Gazette exclaimed “Our people say that the militia system is all a farce… dimagogues have been using commissions in the military as stepping stones to offices of profit and honour, and that a cure must be found for the evil.”

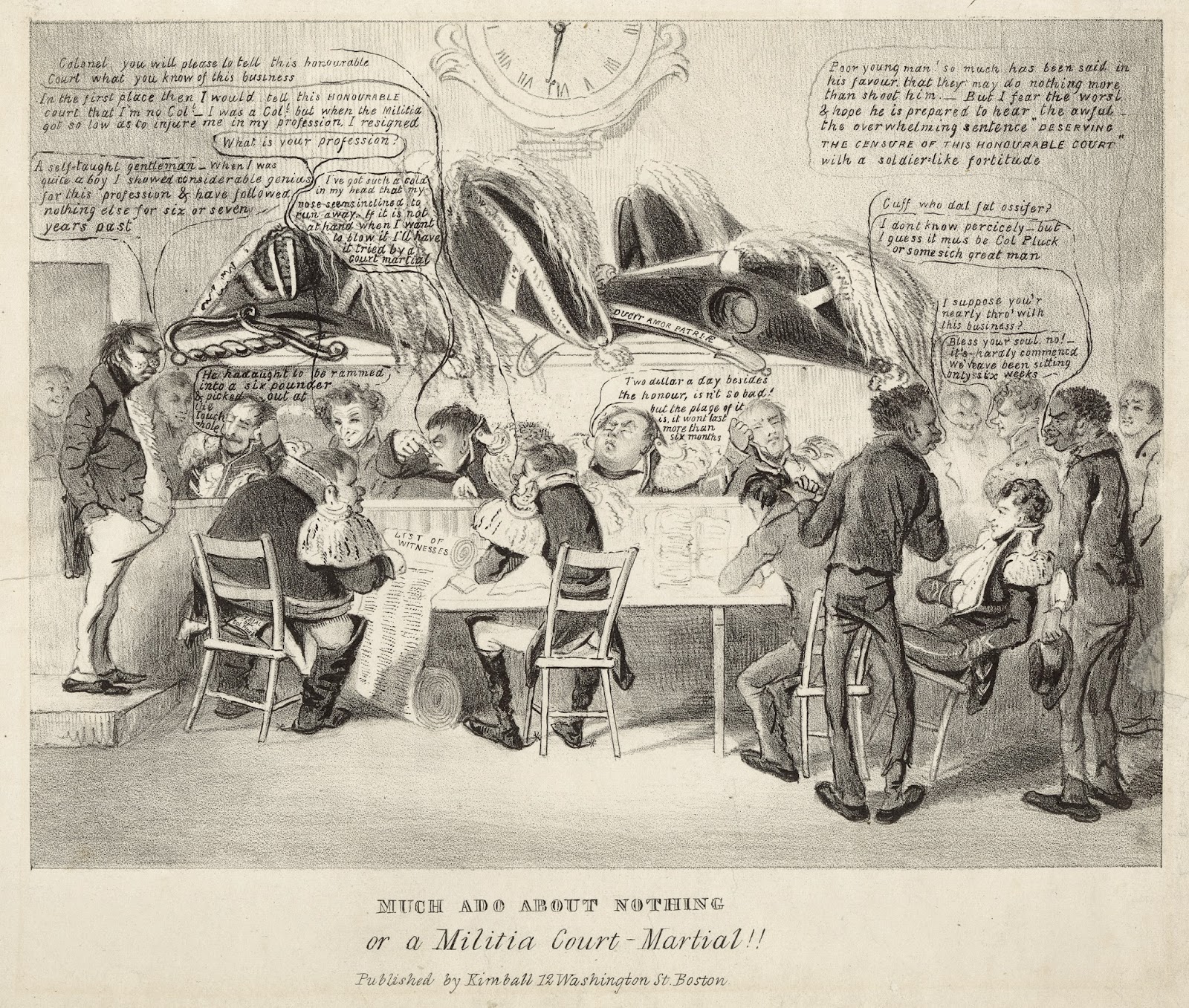

Pluck returned to Philadelphia in 1826 to face court martial and demotion but his removal did nothing to deter the 84th, who determined to top themselves. In 1833 Colonel Peter Albright led the 84th in dress that was frequently described as “fantastical,” with mismatched uniforms of calico, women’s frocks, and huge hats with enormous plumes. The now familiar broomsticks and cornstalks were shouldered along with colossal oversized muskets, broadswords of six to twelve foot length, and large fish. They marched to the music of a penny whistle, each member endeavoring to outdo the next in preposterousness. The Pennsylvania Gazette reported that “To all intents and purposes… the folly and absurdity of our ordinary militia parades was most fully obtained.”

Like Pluck before him, Albright was court-martialed for “unsoldier-like conduct.” His arrest inflamed the regiment which continued to parade as before, but also as knights clad in armor, cavaliers in bearskin, and as Native Americans.” Albright’s surprising acquittal triggered exuberant celebrations where Albright appeared dressed as a Revolutionary War officer with powdered wig, powdered face, and his nose conspicuously browned with shoe polish.

The period of the 1820s and 1830s also witnessed the rising sophistication of American graphic satire. In its infancy during the colonial and revolutionary period, graphic satire expanded in the United States along with a general expansion of printing and publishing. Two of the most prolific American satiric artists, David Claypool Johnston and Edward Williams Clay (1799-1857), produced popular prints commenting upon the militia crisis. Regardless of their opinions on the subject, as satirists, they clearly shared an appreciation for these farcical militias and their use of absurdity to emasculate those in power.

|

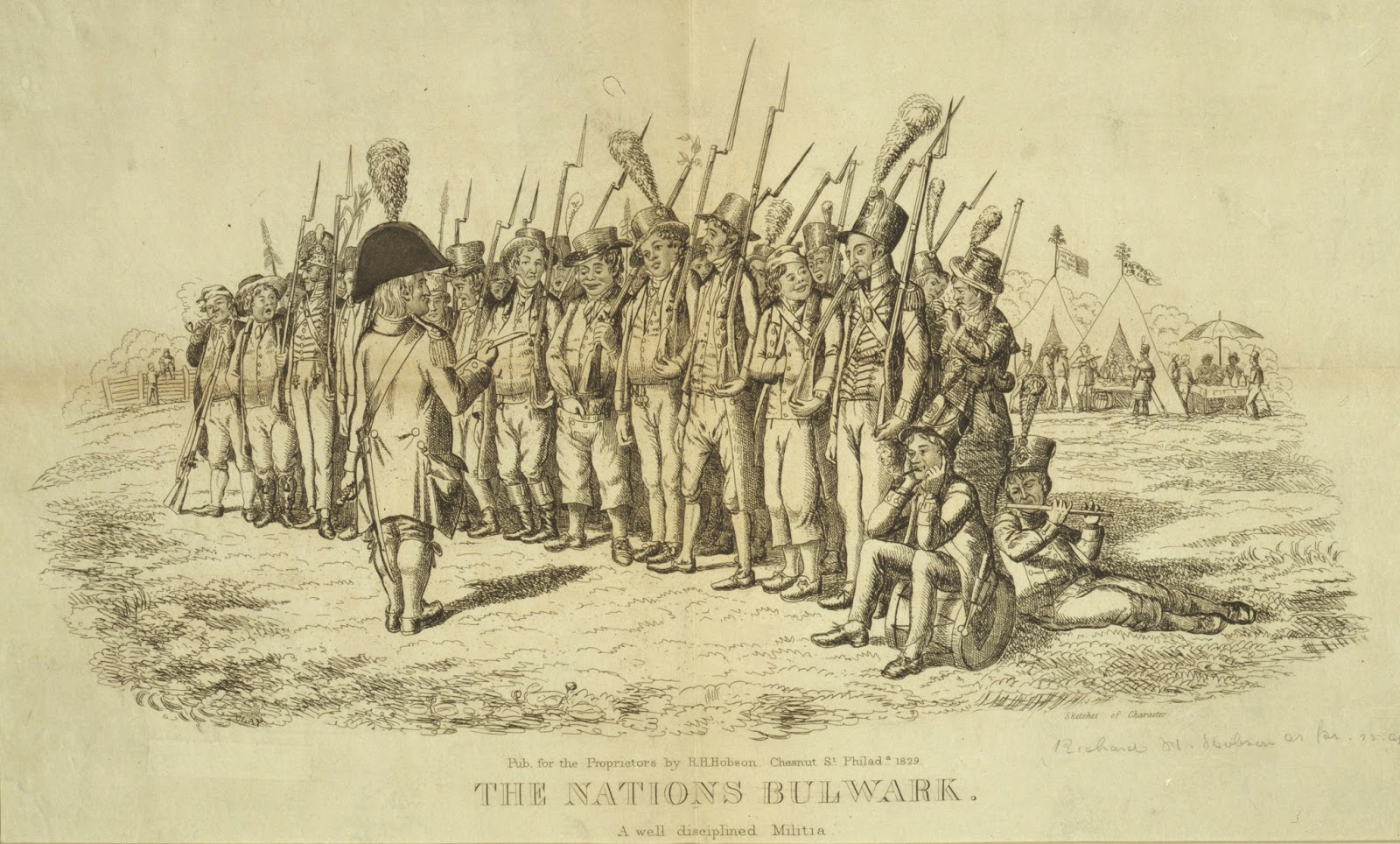

| Edward Williams Clay. The Nations Bulwark. A Well Disciplined Militia. Etching. Philadelphia : R.H. Hobson, 1829. Image credit: The Library of Congress. |

Originally from Philadelphia and later New York City, Edward Clay remains an enigmatic figure. He created highly provocative racial, social, and political satire until late in his life. His 1829 engraving The Nation’s Bulwark, a Well-Disciplined Militia (LC) shows a lineup of bored, undisciplined soldiers smoking pipes, chatting, barely awake, confronted by a plump officer with a bottle bulging from his pocket. The slogans on the tent banners in the background, “Hurrah for Old Hickory” and “Jackson Forever” indicate the unit’s loyalty to Jacksonian principles of democracy.

D.C. Johnston, a talented artist and actor from Philadelphia, then Boston, engraved Col. Pluck showing the Colonel marching in full dress uniform, brandishing his sword, wearing a hat with dangling baubles at each end. The chaos seen behind Pluck includes a soldier riding a cow, others marching with ludicrous banners of men sawing logs and a cow being milked, and of course, cornstalks and sticks as weapons.

Both artists played to an audience of urban consumers of satire, familiar with the tropes of ridiculousness, but here presented with views not at all far from reality — satire ready-made.

|

| David Claypoole Johnston. Much Ado About Nothing, Or, A Militia Court-Martial!! Boston : Kimball, lithographer/publisher, circa 1833. |

Davis, Susan G. “The Career of Colonel Pluck: Folk Drama and Popular Protest in Early Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Vol. CIX (1985).

The New York Commercial Advertiser, May, 1825

The Philadelphia Gazette, May 3, 1825

The Saturday Evening Post May 7, 1825; May 21, 1825

The Democratic Press, May 26, 1825

The Essex Register, May 26, 1825

The Reporter, June 13, 1825

The Geneva Palladium, August 23, 1826

The Pennsylvania Gazette, May 21, 1833