Today in History: Greek Independence Day

Cheney J. Schopieray, Assistant Curator of Manuscripts, has worked at the Clements Library since 2002. His list of favorite manuscripts grows longer on a daily basis, but in honor of the 190th anniversary celebration of the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence (1821-1829), today his favorite manuscript is a public letter written by William Townshend Washington, August 27, 1825. Cheney found (and continues to find) the complexity of William Washington’s character, his at times egregious behavior, and his questionable motives to be intriguing and worthy of a biography, or perhaps an adventure novel.

The letter has relevance to American service in the Greek rebellion against Turkish Ottoman rule and it is an unusual piece of Washingtoniana. William T. Washington was a Virginian, who claimed distant familial ties to George Washington. He attended West Point and received a Lieutenant’s commission in 1823.

Washington, like Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe, was an American Philhellene who traveled to Greece in the 1820s to support the Revolution. However, unlike Howe, his services in Greece are remembered with mixed feelings. Contemporary accounts of Washington variously referred to him as strange, “brave but unprincipled,” and possessed of “unbounded vanity.” [1] Commodore John Rodgers, commander of the U.S. Mediterranean squadron during the Greek Revolution, had occasion to meet Washington under less than favorable circumstances. He described him as “inconsistent, unless he is insane.”[2]

Under the auspices of the Boston Greek Committee and with letters of support from prominent U.S. officials, William Washington traveled to Greece. He arrived in June 1825, “wearing an extraordinary Hussar uniform.”[3] In August 1825, the provisionary government in Greece sent an “Act of Submission” to England, appealing for protection. Meanwhile, Washington had appointed himself “Deputy of the American Philhellenic Committees” and signed an outrageous protest which claimed that the United States supported a French constituency (led by General Roche), seeking to place a member of French nobility on the throne of Greece. The U.S. and French Philhellenic Committees promptly alienated themselves from the protest of Washington and Roche and the two men were roundly condemned by Americans in the U.S. and in Greece.

After sending regrets to the executive council of the Greek provisionary government for their decision, Washington left for Smyrna, a pro-Greek port on the coast of what is now Turkey. By this time, U.S. Naval forces in the Mediterranean were aware of William Washington’s intrigues and Commodore Rodgers intended, “after seeing him and rebuking him for his impudent conduct, to offer him protection” on the condition that “he would not meddle with the political concerns of the place he was then in.”[4] But Washington had already sought protection from the French and wrote a public letter of expatriation, condemning the United States and Americans abroad.

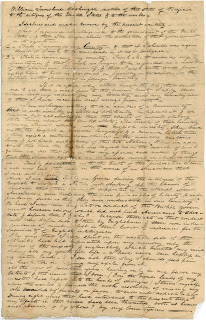

His letter reads in part:

That I renounce my Country – & that if I should ever again revisit it I wish to be considered in it as a foreigner. That in renouncing my country, I wish also to renounce my Countrymen & that I wish no longer to be regarded as a member of the American Community, & that I wish with some few exceptions to hold no personal or friendly intercourse for the future with Americans in foreign Countries.

He proceeded to disparage the United States for its “moral slavery” to England (that is, their support of England’s foreign policy), for financial and other trouble in his early life, and for alleged refusal of protection by Commodore Rodgers.

Despite his erratic behavior, William T. Washington eventually expressed his love of Greece productively in battle. He fought bravely with Fotomaras’ faction which was engaged at Nafplion in the summer of 1827. As he assisted in the bombardment of the fortress of Palamidi, a musket ball struck him in the leg. For treatment, he was taken aboard the British warship, HMS Asia, but did not survive the wound. He died on July 18, 1827, “railing at his native land, ‘wishing her every ill and misfortune,’ and ‘muttering something about Amelia and a lock of hair’.”[5]

Notes:

1. C.W.J. Eliot, ed. Campaign of the Falieri and Piraeus in the Year 1827, or, Journal of a Volunteer, being the Personal Account of Captain Thomas Douglas Whitcombe (Princeton: The American School of Classical Studies at Athens, 1992), 170n.

2. Stephen A. Larrabee. Hellas Observed: The American Experience of Greece, 1775-1865 (New York: New York University Press, 1957), 316n.

3. Douglas Dakin. British and American Philhellenes During the War of Greek Independence, 1821-1833 (Thessaloniki: Hetaireia Makedonikōn Spoudōn, 1955), 108.

4. Larrabee, Hellas Observed, 132.

5. Larrabee, Hellas Observed, 134.