Guest post by Meg Hixon, Project Archivist

The First World War has long been eclipsed in American public memory, but it was, at the time, the “Great War” that affected families across the country and across the world. In honor of Veterans’ Day, the successor to Armistice Day, I would like to highlight some of the lesser-known collections in the Clements Library’s Manuscripts Division. The library holds a robust collection of World War I material, including diaries and soldiers’ letters about the doughboys’ experiences in training camps around the United States and along the Western Front.

Though the United States did not formally enter the war until 1917, members of the American Expeditionary Forces played a pivotal role in the Allied victory, participating in such battles as the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. In their diaries and letters home, soldiers described a range of reactions to news of the armistice, which ended active combat at 11:11 A.M. on November 11, 1918. On the previous day, November 10, 1918, Stewart Frederick Laurent, a native of Pennsylvania who had been drafted into Company 11 of the 1st Air Service Mechanics Regiment, had shared his pride in the Americans’ role in bringing peace:

The French and English and Belgians did wonderful fighting but it seems that after the U.S.A. troops arrived over here that they got new courage and spirit for they are surely walking over the Germans…The world’s history is certainly being made. The German envoys have until 11 o’clock tomorrow to decide about signing the armistice. I hope [they] have sense enough to sign. You will know and so will I know the outcome of these negotiations before this letter reaches you.

On November 12, he joyfully exclaimed, “Just think! Peace is at hand!”

Laurent served behind the front lines, but other American soldiers witnessed firsthand the guns’ instant silence. Ambulance driver Bert C. Whitney vividly counted down the war’s final moments in his diary entry of November 11, 1918, “a day of days and one that we will always remember.” With several minutes to go, he reported, “Our whole front is thundering away as if there was a big drive…they are firing like mad.” A few minutes later, “a terrific volley from all the cannon ended the firing. Every thing is as quiet as can be except for the tolling of bells can it be. I can’t hardly believe that peace can be so near.” Though the end of the war caused widespread elation throughout France, Captain Edward Van Winkle of the 24th Engineer Regiment observed a more muted sense of victory. “The Armistice caused no little work,” he told his wife in a letter dated November 11-12, 1918. “I am almost ready to admit that the French people don’t know how to celebrate, for everything has been serious, calm and…indifferent all day. But that’s another story.”

|

|

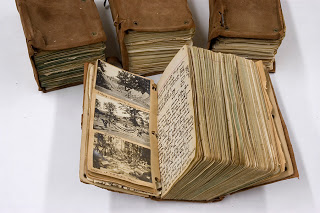

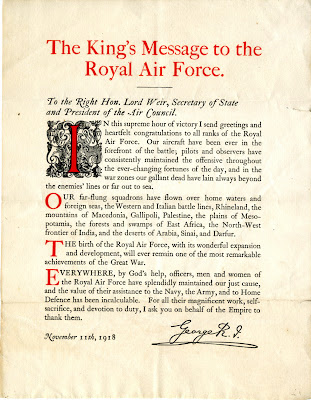

James Leonard Sturgeon, a pilot cadet in the Canadian Royal Flying Corps, received a proclamation from King George V commending the Royal Air Force for its work during the war.

|

Along with these and other collections pertaining to soldiers in France, the Clements’ collections include descriptions of life at training camps around the United States and, in the case of pilot cadet James Leonard Sturgeon, in Canada. Alfred Schaller spent most of the war at Fort Sam Houston, Texas, with Troop F of the 14th Cavalry Regiment. Though he did not go to Europe, he, too, was elated by the end of hostilities. His letter of November 12, 1918, provides a detailed look at the unusual celebrations in San Antonio, Texas (the spelling, capitalization, and punctuation, except ellipses, are all present in the original):

Did you know that the war is over?…Yesterday morning I woke up at four o;clock and I heard a lot of yelling and whistles blowing so I knew that it must be that GERMANY had accepted the U. S. terms,: At 5 O,CLOCK there was an extra out to that effect; Then the fun started; At CAMP TRAVIS the drafted ones started to raise (TEXAS) or rather H___…Of course I went to town after supper; And some night; Talk about noise; And powder; and paint; every body was buying face powder and throwing it in every body’s face and red and black shoe polish dobbing it over every bodys face and they all took it good natured; and those that did not was given another dose; I never saw such a sight: HORNS “BELLS” WHISTLES “POWDER” PAINT “CONFETTI” And every thing imagineable.

For some soldiers, the end of the war meant an eerie, disconcerting quiet on the front lines. For some, the armistice led to a few extra months in France or Germany with the Army of Occupation. For some, such as Brewster Littlefield of the 101st Engineer Regiment, who was killed by a piece of shrapnel on November 3, 1918, the end came too late. November 11, 1918, marked a pivotal moment in the shape of the modern world, one that lives on in the words of those who witnessed it firsthand, and one that we continue to honor and remember 94 years later.