Guest post by JJ Jacobson, Curator of American Culinary History

If Americans have any one person to thank for the Thanksgiving holiday, it is Sarah Josepha Buell Hale. Hale waged a decades-long campaign for the establishment of a national Thanksgiving Day on the last Thursday of November.

She was born Sarah Josepha Buell on October 24th, 1788 in Newport, New Hampshire.

She was educated at home, with tutoring in Latin, philosophy, English, and classical literature by her brother while he was a student at Dartmouth. She remained a strong proponent of education for women throughout her life. When she was widowed in 1822, she turned to literature as a means to support herself and her children. She established her reputation in 1827 with the novel Northwood, in which we already see a Thanksgiving theme emerging: a Thanksgiving holiday forms the background for part of the action, and the Thanksgiving meal is given a chapter of its own.

From 1837 to 1877 Hale was the editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book, a wildly successful magazine for women which achieved a circulation of 150,000 by 1865. Hale used her monthly editorial to advocate for the causes to which she was committed. While she was especially enthusiastic about education for women, she also agitated for women’s employment, a monument on Bunker Hill, making Mount Vernon a national shrine, the elevation of housekeeping to a profession, and of course Thanksgiving.

Hale’s campaign to have Thanksgiving declared a national holiday began in the 1840s. She wrote an editorial about it every year from 1846 on, and corresponded with state and territorial governors, members of congress, and presidents to promote the last Thursday of November as the official day. A typical editorial, from October 1858, said:

“The last Thursday in November falls, this year, on the twenty-fifth. May we not hope that our nation will unite, on this day, in keeping the festival? The Governors of the States and Territories might, by uniting on this day, make the year memorable in our annals to the end of time. Will not the editors of newspapers lead the way in this union of hearts, at our national festival? Then the last Thursday in November would soon come to be considered the American’s Thanksgiving Day, and wherever our countrymen dwelt the day would be a festival.”

The custom gathered force, due in part to Hale’s promotion of it, with many states and territories declaring a holiday on the appointed day. Hale’s efforts finally met with success in 1863, when Lincoln, in a proclamation of October 3rd, proclaimed the last Thursday of November as a national holiday. Subsequent presidents followed suit, and in 1941, a Congressional Joint Resolution officially set the fourth Thursday of November as a national holiday for Thanksgiving.

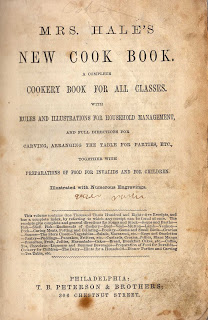

Hale contributed largely to periodicals besides her own and published more than forty volumes of poetry, fiction, plays, biography, household management, and cookery. The Clements has a number of her works, including the 1873 revised edition of her Mrs. Hale’s new cook book : a complete cookery book for all classes with rules and illustrations for household management and full directions for carving, arranging the table for parties, etc. : together with preparations of food for invalids and for children.

Hale contributed largely to periodicals besides her own and published more than forty volumes of poetry, fiction, plays, biography, household management, and cookery. The Clements has a number of her works, including the 1873 revised edition of her Mrs. Hale’s new cook book : a complete cookery book for all classes with rules and illustrations for household management and full directions for carving, arranging the table for parties, etc. : together with preparations of food for invalids and for children.

The book contains recipes the modern cook would recognize for the central dishes of the Thanksgiving meal: roast turkey, stuffing, cranberry sauce, sweet potatoes, and pumpkin pie. It is also a platform for a certain amount of editorializing.

Hale had high aspirations for women as a moral force in the world. She felt women should not directly involve themselves in politics, and therefore opposed suffrage. Rather she advocated women working in their domestic sphere (and in suitable occupations such as teaching) to influence those under their care. The preface to Mrs Hale’s new cook book claims the influence of women in the home as significant work in an important sphere of action:

“Cookery, as an Art, ranks in the highest department of useful knowledge, connected, as it is, with the welfare of every human being.

When understood in all its bearings and conducted on scientific principles, it promotes health and happiness, moral and social improvement, and adds the charm of contentment to every-day life.”

This is a familiar theme for the proponents of Domestic Science, a term Hale coined: women were to make the world a better place by creating an environment that would foster virtue, whereupon virtuous action would diffuse from the home into society.

Hale, like many of the writers and teachers who espoused this idea, was not herself averse to acting on a wider stage, with her editorials, letter writing, and other campaigns for the causes she undertook. If she had been, our Thanksgiving holiday might look very different.