Guest post by Meg Hixon, Project Archivist

Though the Titanic saw her last glimpse of daylight exactly 100 years ago this Sunday, the tragedy continues to fascinate the modern imagination in many ways, both as a symbol of the era’s social hierarchies and customs and as a backdrop for Broadway musicals and Hollywood films. The Clements Library holds several items related to the famous shipwreck, including several letters from Americans sharing their first reactions to the news. Their letters provide valuable insight into the psychological impact of an “unsinkable” ship’s foundering, and touch upon many of the same themes with which the Titanic is associated today.

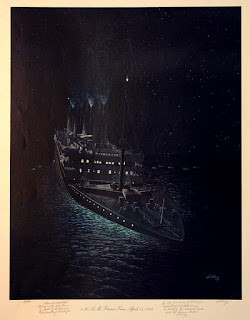

|

| Print by J. Clay, 1:40 A.M. Titanic Time, April 15, 1912. |

Despite the fact that she did not know anyone onboard the ship for its only voyage, Juliana Conover of Princeton, New Jersey, felt personally affected by the disaster due to a previous brush with the ship. Her letter to a young friend, Helen Buchanan, recalls their reaction upon encountering the Titanic in Belfast, Ireland, and shares her concerns about the implications of the sinking:

“Oh, Helen, isn’t it awful beyond words about the Titanic! Do you remember how we leaned over the rail in the dock at Belfast & watched her? That mammoth iron-clad that looked as if it could defy anything. Of course there’s still hope that the accounts are exaggerated. Doesn’t it seem uncanny that the twin of the Olympic should meet with an accident on her maiden trip?…How sorry I feel for the White Star officers. Do you remember how badgered they were when no lives were lost & this is so infinitely worse. So horrible that it’s hard to believe. I hope you didn’t have any friends on board.” (Helen Buchanan papers: April 16, 1912)

James Pinckney Pope, a lawyer and politician in Boise, Idaho, focused on the tragedy itself, and attempted to imagine the final hours of those on board. His letter also shows a poignant reaction to reports of male chivalry, whose legacies are maintained amidst the modern mythology of the disaster:

“What if you had been on board the “Titanic”? I have just finished reading the morning paper, and am filled with horror. It is simply terrible. When we try to imagine the heartbreaks and the untold suffering of those who went down we get sick at heart. From the reports this morning it would seem that the women and children were put in the life boats, while most of the men volunteered to stay behind. Isn’t that fine? Nothing could be more heroic! I’m proud of them. Men are just as brave now as they ever were, aren’t they? They were men, every inch of them. But how terrible it must have been for the wives and daughters and mothers to leave them behind! Such a disaster brings a fellow right down to earth, and makes him feel his awful insignificance. We don’t amount to much, do we? But I’m mighty glad you were not there. I am anxious for the “Carpathia” to arrive and let us know more about it. Oh, those poor fellows! All the tragedies of human life took place there- indescribable, and terrible beyond our conception.” (Pope-Horn papers: April 17, 1912)

The news even resonated beyond the shores of America and Europe. While the advent of wireless transmissions famously contributed to the story of the Titanic’s foundering and to its subsequent splash in the American and European newspapers, the news resonated far beyond the Atlantic world. An American missionary in Ramallah, Palestine, still hadn’t heard full details several weeks after the sinking, though she anticipated the scope of the disaster and, like Juliana Conover, shared her own personal connection to the tragedy:

“We have not yet had American papers concerning the Titanic disaster and surely titanic is the proper adjective for it. If we get anything like the truth it must have been the most awful disaster of modern times. Some tourists that had been here this winter were among the lost the Consul told us. ([Belle Patterson] to Willard Patterson, May 5, 1912)

These powerful contemporary accounts show a remarkable understanding of the scope of the tragedy, highlighting its lasting symbolic significance and emotional power. The intervening century has proven that the story of the doomed liner, a symbol of opulence and hubris and their continuing clash against the forces of nature, continues to resonate today. The grandeur and allure of the Titanic, the great lost ocean liner, has yet to fade.