Guest post by Kayla Carucci, Book Division student assistant and graduate student at the University of Michigan School of Information.

With the move from Ellsworth back to campus finally complete, the Clements staff and volunteers grow more excited by the day for the reopening of the reading room. Relocating the collections served as a reminder of how vast and varied the Clements Library holdings are.

|

| A five shilling stamp from the Thomas Gage Papers, William L. Clements Library, The University of Michigan. |

|

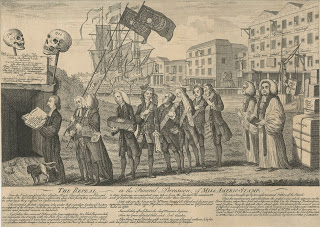

| A popular satirical print celebrates the repeal of the Stamp Act. The repeal, or, The funeral procession of Miss Americ-Stamp (1766). |

|

| The Clements Library owns three different versions of this print; the original was so well received that many printmakers copied it. The repeal, or, The funeral of Miss Ame-Stamp. London: Carington Bowles, 1766. |

American colonial protests began shortly after its passage, escalating into riots in the fall of 1765. Colonists boycotted British goods and attacked the homes of tax collectors and supporters of the Act.

The law became effective in November 1765 and Benjamin Franklin, then residing in London, received sharp criticism in part for his delayed rebuke of the measure. In mid-February 1766, Franklin appeared before the British House of Commons to speak in support of a repeal. A mere four months after its enactment, the Stamp Act was repealed on March 18, 1766. Yet, on the same day, the Declaratory Act passed, setting firmly in place Parliament’s legal authority and supremacy over the colonies.

|

| Revere, P. (1766). A view of the obelisk erected under the Liberty-Tree in Boston on the rejoicings for the repeal of the —- Stamp-Act. [Boston: s.n.]. |

Nevertheless, an obelisk made of wood was erected on the Boston Common as a celebration; candles illuminated it from within. Each side of the obelisk portrayed the colonists’ struggles with the Stamp Act. The obelisk itself became a satirical work of art, and Paul Revere made this famous schematic engraving to preserve it. The bottom of the page reads, “To every Lover of Liberty, this Plate is humbly dedicated, by her true born Sons, in Boston New England.”

|

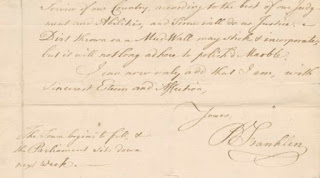

| Except from a letter to Joseph Galloway, from Benjamin Franklin in November 1766. Benjamin Franklin Collection, William L. Clements Library, The University of Michigan. |

Several months after repeal, an exposé essay appeared in a supplement of the Pennsylvania Journal, which attempted to prove that Benjamin Franklin was an author of the Stamp Act, based in part on the knowledge that he had recommended merchant John Hughes, a friend, for the position of stamp distributor in Philadelphia. In an eloquent letter to Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly member/speaker Joseph Galloway, Franklin responded to the accusation.

|

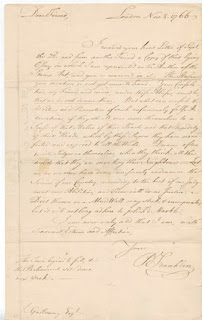

| 1766 November 8 . Benjamin Franklin ALS to Joseph Galloway; London, [England]. Benjamin Franklin Collection, William L. Clements Library, The University of Michigan. |

The letter states: “Dear friend, I received your kind Letter of Sept. the 22d. and from another Friend a Copy of that lying Essay in which I am represented as the Author of the Stamp Act, and you as concern’d in it. The Answer you mention is not yet come to hand. Your Consolation, my Friend, and mine, under these Abuses, must be, that we do not deserve them. But what can console the Writers and Promoters of such infamously false Accusations, if they should ever come themselves to a Sense of that Malice of their Hearts, and that Stupidity of their Heads, which by these Papers they have manifested and exposed to all the World. Dunces often write Satyrs on themselves, when they think all the while that they are mocking their Neighbours. Let us, as we ever have done, uniformly endeavour the Service of our Country, according to the best of our Judgment and Abilities, and Time will do us Justice. Dirt thrown on a Mud-Wall may stick and incorporate; but it will not long adhere to polish’d Marble. I can now only add that I am, with Sincerest Esteem and Affection, Yours, B Franklin”