The Death of General Wolfe was reinstalled for permanent public display at the William L. Clements Library last month. Over 240 years old and 8 1/2 feet in width, the epic Benjamin West painting once again graces its longtime home after nearly seven years offsite. In this essay, Graphics Curator Clayton Lewis describes how William Clements acquired the painting in 1928.

All collectors know the feeling of being haunted by the one that got away. “Buyer’s remorse” from an expensive impulse purchase can hurt, but the pain of having hesitated and then lost is much worse. This was likely how William L. Clements felt after the Sotheby’s auction of February 10, 1921, where he bid $4,000, a huge sum for the day, on a full-size version by Benjamin West of his masterpiece The Death of General Wolfe—but to no avail.

Benjamin West, The Death of General Wolfe (1776)

At the time, Clements was steeped in the design of his proposed Library of Americana, which he planned to build on the campus of his alma mater, the University of Michigan. What better statement of purpose and identity could his collection of early American history have than The Death of General Wolfe hanging high on the oak-paneled wall of the Great Hall he envisioned? Clements must have struggled to put the West painting out of his mind as he buried himself in the complications of constructing the library that would bear his name, the first collection of its kind of rare Americana at an American public university.

Fortunately for Clements and for the University of Michigan, Benjamin West painted five full-size versions of his most popular painting. Across the Atlantic, in Germany, the third version was starting on a course destined to end in Ann Arbor. The Prince Regent of Waldeck, Landgreve of Hesse, had commissioned this painting from West after seeing the original on display in London in 1775. Its themes of national unity, imperial power, and martyrdom must have resonated with the Prince, who had just agreed to send troops to help Britain fight the rebelling colonists in North America, the scene of the painting.

The Prince’s version of The Death of General Wolfe became the centerpiece of the collection at Castle Waldeck in Arolsen, which was filled with grandiose portraits and minor masterpieces. The epic sweep and emotion of West’s painting set it apart from the rest of the rather staid Waldeck collection. Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1752–1840), professor of medicine and natural history at Göttingen University, described the painting in a 1777 letter to his father, shortly after its arrival:

The Castle is very modern, built circa 1720, where lives the Prince of the region and his mother. In a great hall, hung painted portraits of great heroes, statesmen and scholars. What charmed me more than anything was the famous painting by B. West, The Death of the General Wolfe (it cost 600 pounds sterling). The bravery and calm in the dying Wolfe’s face, while at the same time learning about the victory from his men, the numbness and grief in the faces of the surrounding officers, the pensiveness of the brave surgeon who, abandoned by his art, kneels next to him, the astonishment of an American native who is in front of him, all that can be seen from every eye and felt from every heart, but certainly can’t be described by a quill.

The color palette is muted, but one is sure that the hand of the master has moved one, not like the French pictures where one is deceived by the paint box. I stood daily and long in front of it, each time with new enjoyment. The Count has the famous original painting by H. Tischbein, Herman after the Victory over Varus, which clashes terribly with West. Full of forced theatrical arrangements, so little nature, such unimportant faces, such a garish color palette. Luckily, it hangs in another room, one should see it first before West’s so it doesn’t lose so much in comparison.

The painting remained at the castle for 150 years until it was shipped to the New York gallery of Berlin dealer Paul Bottenweiser in 1927. Acting as agent for Waldeck, Bottenweiser Galleries offered it privately to the Smithsonian Institution, but the national collection was strapped for cash and declined to purchase it.

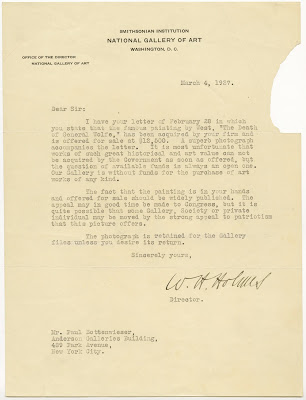

The Smithsonian Institution declines to purchase The Death of General Wolfe in this letter of March 4, 1927.

Another Chance

The William L. Clements of 1928 was greatly changed from the man who failed at the auction in 1921. After the dedication of his library in 1923, Clements had written, “I have returned home to a house empty of nearly all books, so it is needless to tell you how totally lost I am.” There were indications that his marriage was not a happy one and with his son James having died of influenza in France in 1918, he showed signs of loneliness and resentment that would surface periodically for the rest of his life. But in the late 1920s, Clements was rebounding and filling his empty bookcases with manuscript collections of major players from the American Revolution—the collections that would jumpstart reconsideration of that event by twentieth- and twenty-first-century historians.

On April 1, 1928, the New York Times reproduced the Waldeck painting in its Sunday supplement with an announcement that it was on display and available for purchase at Paul Bottenwieser Galleries. Clements was in New York on business, staying at the Hotel Belmont on 42nd Street. He wrote to his library Director, Randolph G. Adams, saying he intended to see the painting immediately: “I am interested in seeing the Benj. West picture of the ‘Death of Wolfe’ now on exhibition here and reproduced in today’s (Sunday) Times. It is probably very expensive…. It would be a wonderful hanging for the large room but I must stop my extravagance.”

Clements was deeply moved, however, by the stunning painting and its wonderful condition. Bottenweiser Galleries told Clements that the picture was “never retouched in any way, only washed in clear rainwater and varnished.” The provenance was rock-solid and fascinating in and of itself, especially to a collector of American Revolutionary materials. The significance of this particular painting’s having come from the collection of a provider of Hessian soldiers that fought General Washington was certainly not lost on Clements.

Ever the shrewd businessman, Clements risked making an offer of $7,500—much less than the asking price of $12,500, but considerably more than his failed bid of $4,000 at the Sotheby’s auction. While his offer may seem modest in the extreme compared to today’s overinflated art market, Clements had purchased one of the most famous rare books in his collection, the Rome 1493 edition of Christopher Columbus’s Epistola, for $1,650 a few years earlier and the construction budget for his luxurious library of cut sandstone, carved oak, and polished brass was $175,000. Julius Roedelsheimer wrote to his client in Waldeck for a response to the offer while Clements headed back to his Bay City home to wait.

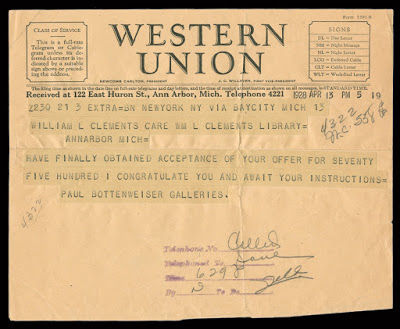

On April 7, 1928, Paul Bottenwieser Galleries sent Clements a wire to report that there was no news from Waldeck. Six days later, they congratulated him—the price was agreeable and the owner would include with the painting a letter from 1776 that accompanied the original purchase receipt from Benjamin West. Clement asked his trusted advisor, New York City book dealer Lathrop C. Harper, to deliver the check for payment and oversee the crating and shipping of the painting by railway express. The Death of General Wolfe arrived in Ann Arbor by the end of April 1928. Randolph Adams had the frame repaired and re-gilded and ordered a special light fixture to illuminate the painting more effectively. On June 8, 1928, he wrote to Clements to let him know the painting was on the wall in time for University commencement visitors, including Lathrop Harper, who would receive an honorary degree. There is no record of how many visitors came to see Clements’s new purchase, but the Library set up velvet ropes in the Great Room to control crowds.

The telegram announcing the acceptance of William Clements’s offer for The Death of General Wolfe.

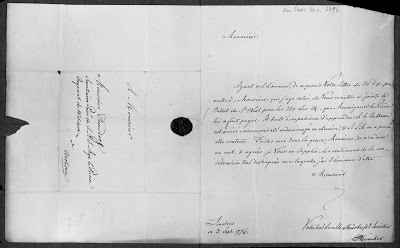

The cover letter dated September 3, 1776 from C. H. Hinuber to the Prince Regent of Waldeck’s secretary that accompanied the original 1776 purchase receipt from Benjamin West. Though promised to William Clements upon his purchase of the painting, it was never delivered. Photostat courtesy of Preussisches Staatsarchiv, Marburg, Germany.

Home at the Clements

Still hanging high on the oak-paneled north wall of the Great Hall, The Death of General Wolfe is breathtaking. Not only does the painting add to the unique aura of the institution, it contextualizes the scope of the collections. It is a highly visible signal that the Americana collection one is entering has an orientation different from the Massachusetts Bay-Jamestown view of early American history offered by many East Coast institutions. The Clements Library collection has a broader perspective that focuses on the swing of power from Native American to French to English, from the Atlantic to the Old Northwest, reflecting both the interests of an early twentieth-century Michigan industrialist and the range of historical scholarship at a great midwestern university.

In spite of the impression that it seems to have made, Clements showed concern that his purchase was not having the effect that he had hoped for. Adams reassured him that

with regard to the degree of appreciation shown the West picture—I would say there is nothing in the library which has excited greater interest among the casual visitors. Among the academic sort of callers, the presence of the West picture has had a rather unexpected and distinctly gratifying effect. More than one has remarked, ‘Now I see why Mr. Clements has given this library.’ This, I take it, means that previously the Library had meant to some of them only a collection of tools—whereas now its more spiritual and less intellectual aspects begin to dawn upon them.

Since Benjamin West’s theory of “epic representation” in historical depictions gives license to the fictionalizing of historic events in artistic depictions, what does it mean for the Clements Library, an institution that stakes its reputation on authentic primary source documentation, to display a powerful fictional rendition of what historian Fred Anderson has called the “most important event in eighteenth century North America?” It very much depends on whether one is seeking documentation of the facts of the event itself or facts of the event’s larger meaning and influence. As evidence of conventional military history, West has given us a very misleading image. But as evidence of the power of visual culture to shape perceptions of history, the conscription of art to the cause of patriotism, the emergence of an independent American identity, the rise of American influence on European culture, and of European participation in the American Revolution, The Death of General Wolfe is an articulate and convincing “document.”

As for the significance of the event itself, University of Michigan Professor Emeritus of History John Shy has said, “Viewers of this painting have always seemed to sense that this dramatic tableau of mourners grouped around a dying young general signifies a major turning point in modern history. The British victory at Québec came close to deciding the future of North America. With the elimination of the French threat, the American colonists soon grew obstreperous and, before long, were confronting the British government. The line between Wolfe’s victory and Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence is not simple or straight, but surely there is a close connection.”

A vital part of the Clements Library’s mission is to provide not just access to information, but the meaningful immersion in historical materials that comes closest to replicating time travel. Its mission is thus as much about inspiration as it is about information. The Death of General Wolfe, “a stupendous piece of drama,” according to Professor Simon Schama of Columbia University, and “a spectacle presented to raise and warm the mind” according to Benjamin West himself, has often ignited that spark of brilliance in scholars working at the Clements, whether specifically on the painting or on other eighteenth-century subjects.

Since 1928 the Clements Library has collected examples of the theme of the death of General Wolfe in popular culture, such as this circa 1810 Wolverton, England-painted iron tea tray.

Since 1928 Benjamin West’s The Death of General Wolfe has left the Clements only for conservation and repair at the Detroit Institute of Arts in the 1980s, to serve as the gateway piece of the 1993 exhibition Picturing History: American Painting 1770–1930 in New York and Washington DC, and now to anchor the University of Michigan Museum of Art’s Benjamin West: General Wolfe and the Art of Empire. It remains in magnificent condition, and many more have now, like Johann Blumenbach, “stood daily and long in front of it, each time with new enjoyment.”

Clayton A. Lewis

Curator of Graphic Materials

2012

(Reproduced with permission, Carole McNamara with an essay by Clayton A. Lewis, “Benjamin West: General Wolfe and the Art of Empire.” UMMA Books, University of Michigan Museum of Art, 2012.)