Guest post by Jean Franzino, Clements Library 2019 Norton Strange Townshend Fellow

* * *

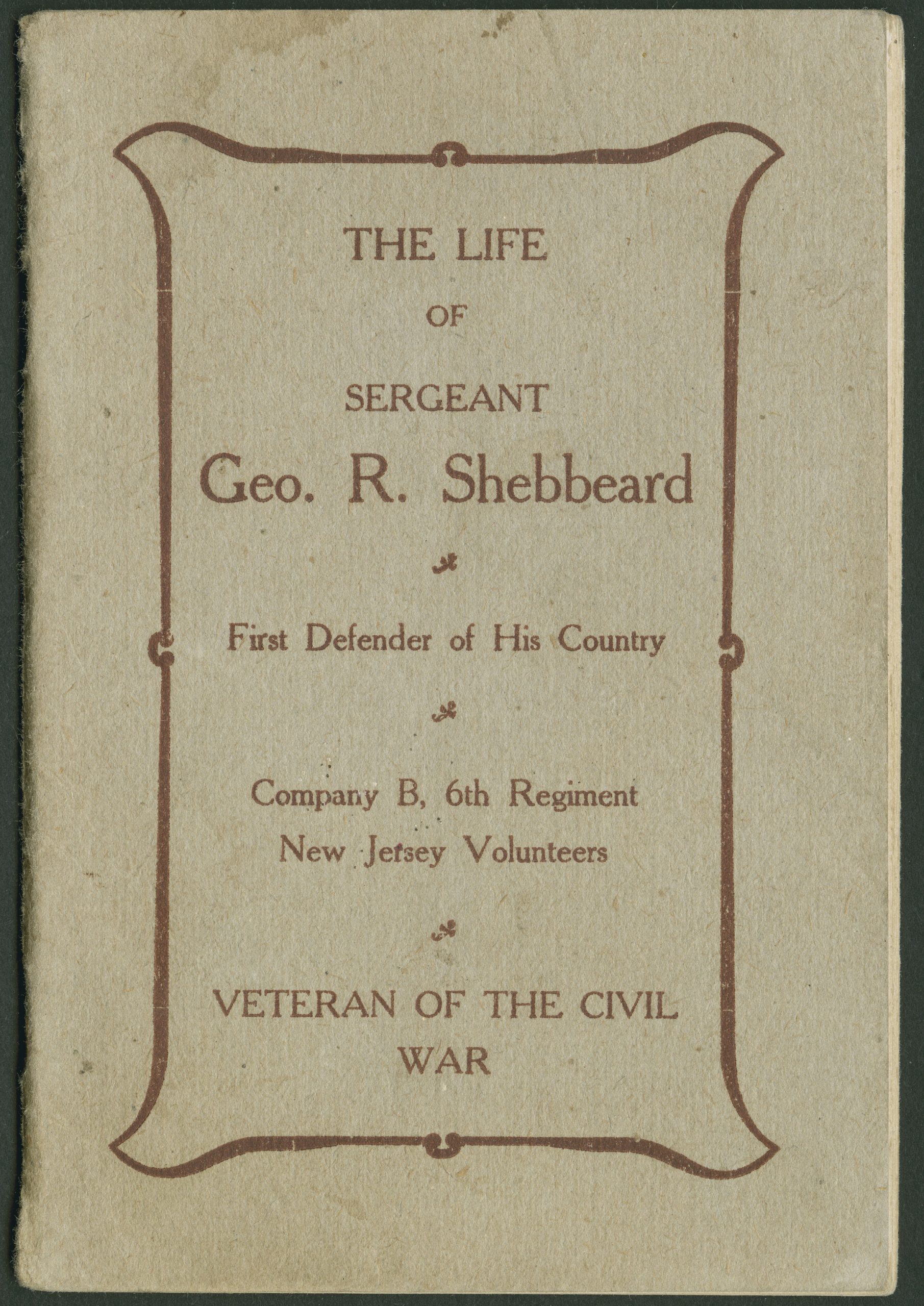

In 1904, New Jersey Civil War veteran George R. Shebbeard published his life narrative, a 32-page booklet of the sort sold by disabled veterans for their economic support. The Clements Library’s copy of the text includes a photograph of Shebbeard, lying in the wagon that serves as his mobility aid, in which he faces the viewer and presents a calm smile. The note printed on the back of the photograph reads:

Sergt. Geo. R. Shebbeard

Co. B., 6 Reg. N.J. Vol.I was injured at the battle of Fair Oaks, June 1st 1862.

I have been helpless for 17 years.

I have lived in this little wagon 20 inches wide, 52 inches long for 10 years, and never get tired; I am 64 years old. I have traveled since 1892

Attended 8 G.A.R. Encampments.

Aug. 25 1904. [1]

Photograph of George Shebbeard with biographical note on the reverse side. An image of Shebbeard lying in his wagon is also reproduced at the opening of his narrative.

Shebbeard’s note presents a curious mixture of dependence and independence, suggesting the careful presentation of self that he aimed to navigate. On the one hand, Shebbeard asserts, he is “helpless”; on the other, he highlights his mobility and activity. Proclaiming that he “never get[s] tired,” a phrase which he repeats several times within the text itself, Shebbeard reverses associations of disability with inability and, arguably, re-values his mobility device. If life in a wagon means a life lived within the confines of a 20 by 52 inch space, it is also that very vehicle which allows Shebbeard to experience the world and even to avoid the exhaustion that might be experienced by nondisabled readers. In this way, Shebbeard asserts some autonomy and narrative agency.

Shebbeard’s text is one of a number of so-called “mendicant texts,” or texts produced in order to solicit financial aid, written or sold by Civil War soldiers who were injured in the service.[2] These texts provide insight into one way that Americans attempted to deal with the economic consequences of sickness and injury in a time before federal social welfare measures such as Social Security Disability Insurance, which began paying monthly benefits to disabled people in 1956.[3] Not entirely disconnected from today’s economy, however, these texts also invite parallels with current measures such as GoFundMe campaigns launched by patients or their loved ones following protracted illness or injury. In both cases, individuals aim to craft a compelling narrative that explains their situation, gains sympathy, and secures economic support from readers.

“The life of Sergeant Geo. R. Shebbeard, first defender of his country. : Company B, 6th regiment, New Jersey volunteers. Veteran of the Civil war.” (1904)

I came to the Clements Library, with the generous support of the Norton Strange Townshend fellowship, to study the representation of disability in Civil War cultural materials. I am interested in how the war impacted Americans’ understanding of disability, given the widespread and visible physical suffering that it caused. As doctor, poet, and cultural commentator Oliver Wendell Holmes put it in an 1863 Atlantic article on the war, “It is not two years since the sight of a person who had lost one of his lower limbs was an infrequent occurrence. Now, alas! there are few among us who have not a cripple among our friends, if not in our own families” (574).[4] Before researching at the Clements, I had encountered many examples of songs, poems, and engravings that celebrated or mourned the amputee veteran’s “empty sleeve” as a figure for his sacrifice. In this vein, the Clements holds a mendicant narrative by Massachusetts veteran Henry Meacham, entitled The Empty Sleeve: or the Life and Hardships of Henry H. Meacham, in the Union Army. By himself, which recounts Meacham’s service and the battle injury that leads to the amputation of his right arm. The narrative was sold by the author for 25 cents.[5]

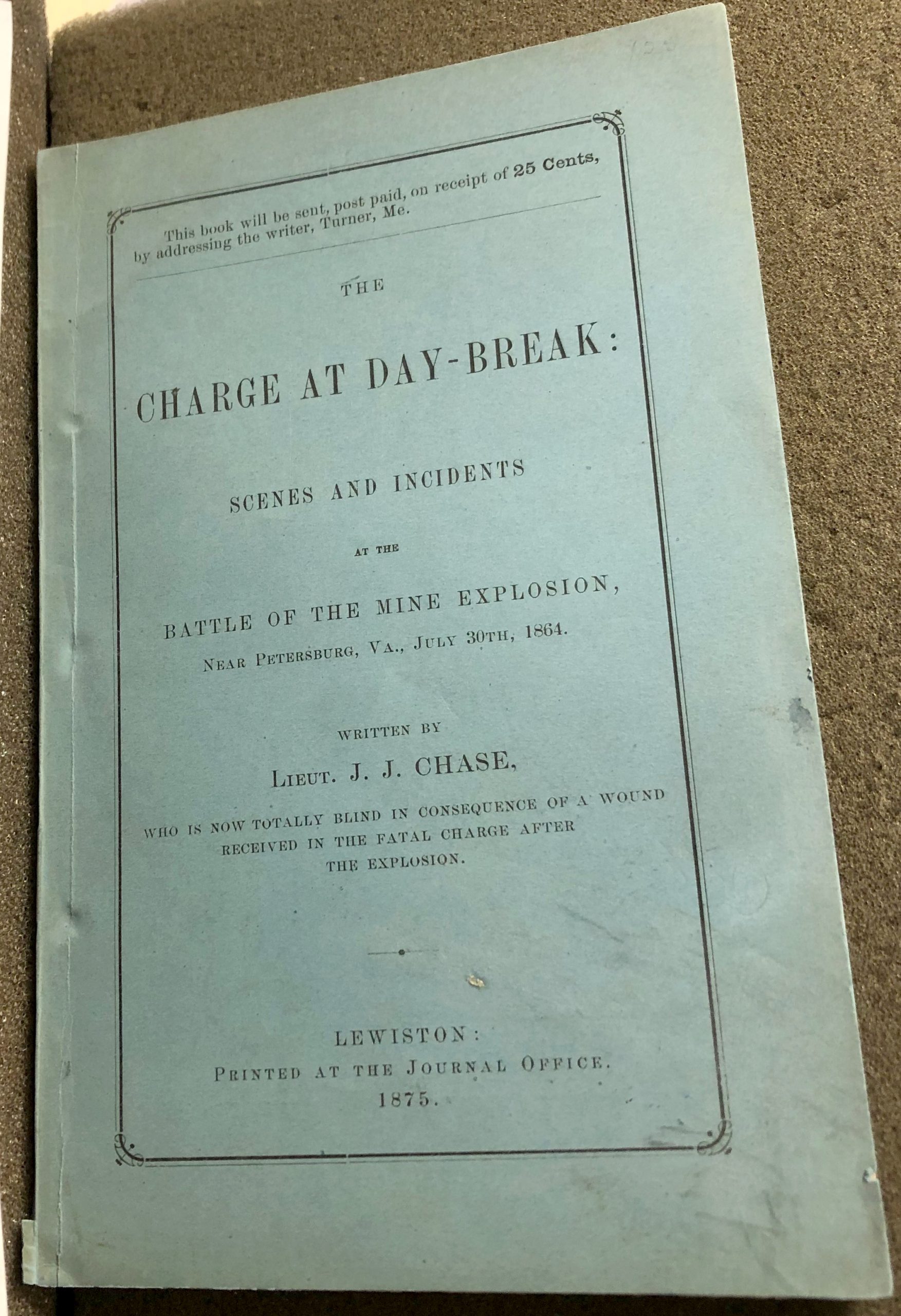

At the Clements, however, I was struck by several narratives by disabled soldiers that fall outside of the expected “Empty Sleeve” trope: narratives by Shebbeard, who received an internal injury after falling from a horse while on military duty; James Judson Chase, a Maine veteran who became blind due to injuries incurred in battle; and George E. Kendall, a Confederate veteran from Virginia who refers to an injury “somewhat similar to that which befell one Uncle Toby, in Flanders,” referencing the character in Laurence Sterne’s novel The Life and Adventures of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759) who receives an injury to the groin (8).[6] These writers faced the additional obstacle of writing from positions that did not conform to public expectation of what a war injury looked like. (Kendall also faced the potential additional obstacle of gaining sympathy from Northern readers when he had fought against the Union.) In this light, the photograph of Shebbeard lying prone in the wagon can be read as making his invisible disabilities visible to a reading public accustomed to picturing disability in the form of the Empty Sleeve.

The Clements Library’s Civil War mendicant materials provide a window into several aspects of the experience of disability in the nineteenth century. Both Shebbeard’s and Chase’s narratives make clear that their disabling was not a one-time event, but a process. While Shebbeard was initially injured in 1862, a moment twenty-five years later proves as much of a climax in his text. He writes, “Sunday, December 17, 1887, I sat all day in a large rocking chair, I could not sit still, I had so much pain where I was injured…At four o’clock I was taken with spasms. I gave a scream” (Shebbeard 23-24). Shebbeard dates the beginning of his truly invalid life to this moment. In Chase’s narrative, as well, a later loss of function in 1872, when acute inflammation from his injuries finally destroys his sight, commands as much of a prominent place in the text as that of his initial wounding (31). In this way, the texts by Shebbeard and Chase challenge the narrative logic of many popular cultural accounts of disabled soldiers, which emphasize the wounds of war as tokens of past sacrifice or bravery. In such accounts society need only honor, rather than accommodate the disabled soldier; Shebbeard and Chase’s narratives, however, point to the ongoing effects of the war on their bodies and thus their need for an external response.

“The charge at day-break: scenes and incidents at the battle of the mine explosion, near Petersburg, Va., July 30th, 1864 / written by Lieut. J.J. Chase, who is now totally blind in consequence of a wound received in the fatal charge after the explosion. “(1875). Full text available via University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Chase’s narrative also provides interesting insights into how the words and attitudes of others can influence one’s experience of disability. Chase recounts how, en route from Washington to his home in Maine following his facial wounds, he encounters a woman in a carriage who “screamed, ‘Don’t let him come in here; I can’t ride with such a horrid looking-creature’” (28). Calling for a mirror from his father the next day, Chase is “saddened and discouraged at what [he] saw,” and, “with the words she had uttered still ringing in [his] ears,” strains to identify any resemblance between his former self and what the mirror had revealed (28). Just then, however, his father reads aloud an account in the Portland Press which speaks approvingly of Chase for his bravery during the explosion near Petersburg, Virginia that maimed him. “In my present state of health and low spirits it was cheering to be thus noticed by my comrades at the explosion,” Chase writes, “and with coming strength my mind was diverted to pleasanter things than my misfortunes. I recovered rapidly, and at the end of three months the ladies did not call me that ‘horrid looking creature’” (30). Chase’s account shows how not only the medical, but the social, aspects of Civil War disability affect him, with the words and attitudes of others playing a large role in his self-conception.

Finally, texts written by disabled Civil War soldiers suggest the extent to which writing offered them both a means of shaping their stories and possible limitations on the forms those stories could take. Shebbeard writes that he has “traveled a great many miles and seen a great deal of the country and have had many people around my wagon and have always tried to do them some good” (27). While this statement reverses the expectation that care flows only in one direction, from the nondisabled to the disabled individual, one also senses an urgency in Shebbeard’s narrative to prove his moral upstandingness and to assert a didactic value for his narrative. More directly, Henry Meacham’s final paragraph is structured by rhetorical swerves that suggest certain constraints on his writing. Meacham criticizes the “large number that have made themselves independently rich out of this war, that would see the soldiers starve before they would lend a helping hand.” He ends the paragraph, however, on a conventionally patriotic note, asserting, “Long may the stars and stripes wave, o’er the land of the free and the home of the brave” (32).

Overall, these materials—part of the Clements Library’s strong holdings in the area of military history—demonstrate in vivid fashion the hardships facing disabled Civil War soldiers in a world not designed to accommodate them, the effect of societal response on veterans’ sense of their own disabilities, and the ingenuity of these writers in attempting to harness the medium of language to better their lot, even in the face of considerable narrative and social obstacles.

— Jean Franzino

2019 Clements Library Townshend Fellow

* * *

[1] Shebbeard, George R,. The Life of Sergeant Geo. R. Shebbeard, First Defender of His Country.: Company B, 6th Regiment, New Jersey Volunteers. Veteran of the Civil War. The Gem Printing Co. (Newark, N.J.), 1904.

[2] For the term “mendicant” as used by booksellers, see John Cumming, “Mendicant Pieces,” American Book Collector Vol. XVI, no. 7 (March 1966): 16-19. Shebbeard’s text has the latest publication date of the Civil War mendicant texts I have consulted.

[3] Shebbeard, like a number of other Civil War mendicant narrators, did receive a disability pension from the government. However, these payments were not necessarily sufficient to support a veteran and his family. As mendicant narrator Henry Meacham put it, “I have often had it said to me, ‘You draw a pension.’ My reply is, I do; but what are fifteen dollars a month toward the support of a man and wife” (32).

[4] Oliver Wendell Holmes, “The Human Wheel, Its Spokes and Felloes,” Atlantic Monthly (May 1863).

[5] Meacham, Henry H. The Empty Sleeve: or the Life and Hardships of Henry H. Meacham, in the Union Army. By himself (Springfield, MA),1869.

[6] Chase, J. J. The Charge at Day-Break: Scenes and Incidents at the Battle of the Mine Explosion, near Petersburg, Va., July 30th, 1864. Printed at the Journal Office (Lewiston, ME), 1875; Kendall, George E., An Humble Belisarius; or The Life of a ‘Johnny Reb.’ By ‘Sonander.’ Brewer’s Book and Job Printing House (Louisville, KY), 1887.